I’ve been going to SMART Adventures since 2018. As a way to get myself doing things on a motorcycle that I don’t get to do on the road, it’s a great opportunity to expand your riding skills. Getting experience on a variety of different bikes is never a bad thing either.

I’ve had some great days at SMART. A particular highlight was during the deepest, darkest summer of 2020 when I did a full day that started on a trials bike, moved to a brand new GS1250 and ended on a dirt bike. It was a great day of bike learning across three very distinct machines.

Last summer we managed to squeeze in a half day and it was the first time I’d done the expert riding group, which I second guessed myself on being in. Unfortunately the father who dragged his son into it wasn’t so introspective. I spent a good amount of money hoping for expert riding opportunities but the afternoon consisted of watching this kid fall off a bike too big for him that his dad kept demanding he ride, and then watching him drop the second bike we had to go back to get for him into a two foot deep puddle. We ended up spending most of the afternoon picking this kid up or riding back to the base after he broke a bike. I needed this trip to SMART to be a win after that last disappointment.

We tried to arrange a trip up in August but things got complicated (dog died, kid going to college, in-laws being difficult) and it never came into focus. I thought this would be our first year not going up to Horseshoe Valley, but Max’s reading week was at the end of October and the week before the weather looked like it might hold up, so I signed us up for an afternoon, and this time SMART nailed it, though in fairness it’s not their fault if a toxic dad wants to design a miserable afternoon.

Going this late in the season and during the school year means you’re less likely to trip over father/son drama. Max got Dave who was the instructor who taught him both ATVs and dirtbikes previously, and I got Tyler who I hadn’t had before but is an incredibly talented off road rider who also has a knack for finding where I was at in terms of skill and then keeping us at that edge throughout the afternoon – I learned tons.

|

| Having a look around before the ride out, it’s not easy keeping the jealousy in check when it comes to SMART Adventures owner Clinton’s bike collection. |

|

| Why are y’all wearing rain jackets? ‘Cause it was raining… a lot! That’s inches deep mud. |

We started with some warm ups in the bowl at the base. I’ve been on a 250 CRF Honda before but this time they had a Kawasaki KLX 300 with bar risers which fit me even better. Tyler had me doing riding with one hand while standing up (in mud), which isn’t as easy as it sounds, then rear wheel lock up braking, then both wheels coming as close to locking up the front as we could manage (in the mud). We also did logs and tires, but once Tyler had an eye in on where I was with clutch control and balance we took off into the woods, which were spectacular!

Riding in a thick ground layer of leaves is tricky. You can’t see rocks or mud underneath, but it teaches you to ride looser and float over the surprises without over correcting for them. We did a lot of kilometers through the rain and brilliant colours and the riding was never dull.

I’m always surprised at how physical proper off-roading is. With mid-teens temperatures and the rain gear on I was dripping wet with sweat. I worked hard at using my legs to grip the bike so my arms weren’t putting pressurized inputs through the handlebars. It’s a combination of balance and lower body strength that demands a lot of energy. One suggestion was to turn my feet fractionally into a corner to weight the pegs in the direction I want to go (a Clinton Smout move) and it works!

We got back for a break but before I parked the Kwak we did K turns. The idea is if you get stuck going up too steep a hill you let the bike stall in gear (or kill the motor in gear) and then roll it backwards leaning into the hill and letting out the clutch bit by bit as you turn the back end until you’re parallel with the hill (still leaning up it). The tricky bit is once you’re near parallel having backed up on the clutch, you start turning the handlebar lock to lock and the bike’s nose will fall under the twisting to face downhill. You then stand it up and roll on down. The final move was to bump start the bike. You do this by leaving it in third gear and dropping the clutch at the bottom of the hill as you sit down on the seat. It sounds like a lot of gymnastics but I got it to work on the second try. Tyler said it can really save your bacon if you get stuck on a big adventure bike on too steep a hill.

Just when I thought it couldn’t get better, Tyler went and got a couple of the new Surron electric dirt bikes out of the lockup. He gave me the bigger Storm model and then told me (jokingly) not to get it wet. We left both bikes in economy mode because of all the wet leaves over mud. Tyler described ‘S’ Mode as ‘scary’, and don’t press turbo!

|

| 383 ft/lbs of torque in mud and wet leaves? What could go wrong?!? |

I hadn’t dropped the big Kawasaki all afternoon despite the crazy conditions. I should have four times but saved it each time. Being able to practice saves is one of the best parts of SMART. I genuinely got to do things on a bike I’ve never done before, which is the whole point. Sounds ominous, right?

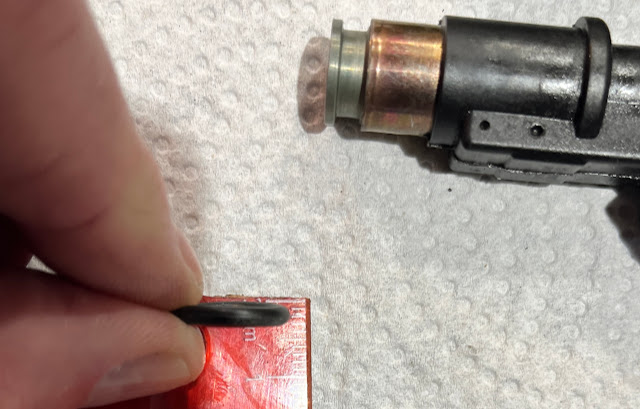

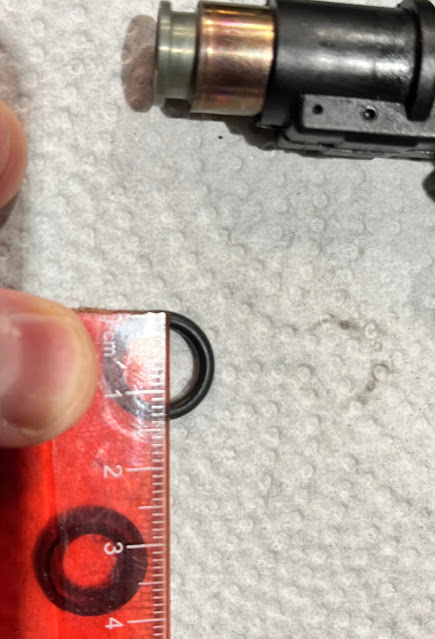

We got out into the woods again and both Tyler and I were down in the first five minutes, but not because the Surron was a torque monster (it’s actually easy to get the hang off). It’s the lack of clutch after riding one all day that caught me out. I was sliding down the muddy side of a trail covered in leaves and went to pull in the clutch to drop a gear, except the clutch is the rear brake and the Surron doesn’t have gears. The bike was out from under me in an instant. Here’s a pic from right after – check out that mud!

I finally got myself back on the bike after I slipped in the mud again throwing a leg over it and we went down a second time. The bike took a minute to ‘re-arm’ because I’d popped one of the brake sensors out, but Tyler figured it out and we were off again.

|

| We made tracks after we both learned not to use the rear brake like a clutch. |

|

| That’s Tyler – ace instructor! |

|

| Interesting choice of name, great bike! |

No one went down again and by the end of a forty minute blast through the woods and into the trails beyond the SMART owned land, I was getting a feel for the Surron (not Sauron from LotR). Being able to focus on riding without worrying about gears and clutches was one part of it. By the end I was getting crafty with the hand operated brakes. The other piece is the silence. When you goose it the bike roosters dirt like a mad thing, and it’s properly quick. The only noise it makes is once you’re up to speed and it’s a ghostly whine, which suited the October hallowe’en woods. I could hear rain hitting leaves as we whispered through the trees.

Where am I at with an electric dirt bike? If I owned a Surron I’d play with the settings so the energy recovery/gearing pulled a bit more and provided more of what feels like engine braking. That would have prevented the spill on the hill. So much of dirt biking is clutch though. You manipulate the clutch continuously to offer smoother power delivery, especially in tricky conditions. A dirt bike without a clutch and gearing is missing a key control, not to go faster, but to manage the power better. The throttle on the Surron felt a bit wooden after riding the big Kwak all afternoon, but that may well have been because I couldn’t feather the Surron’s power delivery with a clutch..

The upside is the silence when riding, though it isn’t really silent with that ghost whine. It did make me miss the thud of the thumper, and the simplicity of the controls (no clutch, no gears) lets you concentrate on other things, but at the cost of simplifying the riding which I have mixed feelings about. Aesthetically, a bike having a heartbeat is pleasing, though I could get used to that ghostly howl.

The older much used Kawasaki went through all sorts of gymnastics during the afternoon without missing a beat, while the Surron needed TLC after one drop, which doesn’t bode well for its resilience. I’d describe my first time on an electric dirt bike as interesting, but they’re not ready for prime time yet. If I were to buy a dirt bike tomorrow it would be a fuel injected ICE model that is decades into its evolution rather than an ebike that’s at the beginning.

SMART was running a regional trials event that weekend and I asked Tyler about electric trials bikes, but he said most riders are still using ICE models – once again because the clutch offers much more nuanced control. I suspect electric bikes will end up adopting something like a clutch to allow for that finer control, though they don’t need gears so perhaps the clutch is simply another electronic intervention. It’s just a matter of time for this to all get worked out, but they’re not quite there yet.

As we pulled in to SMART a red fox fan across the parking lot, and I saw wild turkeys and what might have been a coyote in the woods. We clambered out of our muddy gear past 4pm and got changed before heading up the road to Vetta Nordic Spa where we put our aching muscles into various hot waters as we watched the moon rise through the skeletal trees. Yes, the rain stopped and clouds blew over pretty much the minute we stopped riding, but the weather is part of what made it such a good afternoon of riding! As a way to wrap up the riding season (it was snowing the following weekend), there are few better.

You should go!

from Blogger https://ift.tt/wALiW70

via IFTTT