| Ah, the wisdom of the internet… |

This article on how motorcycles might be less green than you think was shared by Zero motorcycles online. A number of people underneath the article posted responses that had little to do with the article and more to do with a general hatred of motorcycles. The loud pipe crowd seems to raised the ire of the general public quiet effectively. Thanks for that.

I’d heard about the Mythbuster motorcycle pollution test mentioned in the article previously, and had seen annoyed responses pointing out how unfair it was. I felt obliged to put something up that wasn’t just angry motorcycle ranting.

“The Mythbusters they refer to compared a 1990s family sedan to a 1990s Honda super bike. A fairer comparison would have been an 90’s Corvette vs. the Honda super bike (vehicles with similar performance and intent), but then it wouldn’t have been close. The other comparisons were equally unfair. It seemed to be the result of what they had handy, and one of the mythbusters was a sports bike guy, so that’s what they used.

If you think hybrids are the magic bullet you should look into how current battery technology is created and retired, it isn’t pretty. An accurate accounting of the e-waste from hybrid production and operation overshadows their minimal pollution output – you’re basically showing a green face to what is a very polluting industrial process. That hybrid vehicles are utterly tedious and heavy because they carry redundant power trains is yet another problem; heavy things are never efficient.

The idea that some bike owners remove pollution gear for performance is no less true for four wheelers – except when the idiot on my street straight pipes his massive Dodge pickup you can actually see the hole he’s making in the sky. Meanwhile I’ll keep getting 50+mpg out of my Triumph Tiger.”

After that I started poking around to try and get a feel for just how magically ecological electric vehicles are. It turns out lithium based batteries are nasty, both to create and to recycle:

http://www.technobuffalo.com/2012/03/30/why-hybrids-and-evs-dont-help-solve-the-energy-conundrum/

http://www.digitaltrends.com/cars/hold-smugness-tesla-might-just-worse-environment-know/

http://transweb.sjsu.edu/project/1137.html

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lithium-ion-batteries-hybrid-electric-vehicle-recycling/

http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/news/2013/10/what-happens-to-electric-car-batteries-when-the-car-is-retired/index.htm

https://www.iea.org/newsroomandevents/graphics/2015-04-28-carbon-emissions-from-electricity-generation-for-the-top-ten-producer.html

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214993714000037

http://www.mai.org.my/ver1/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1934:recycling-the-hybrid-battery-packs&catid=42:global-auto-news&Itemid=165

“EVs that depend on coal for their electricity are actually 17 percent to 27 percent worse than diesel or gas engines. That is especially bad for the United States, because we derive close to 45 percent of our electricity from coal. In states like Texas, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, that number is much closer to 100 percent.”

“The initial production of the vehicle and the batteries together make up something like 40 percent of the total carbon footprint of an EV – nearly double that of an equivalent gasoline-powered vehicle.”

We live in a time of compromise, but thinking that you’ve somehow solved the entire vehicular pollution thing by leaping into a hybrid or EV sourced from parts delivered by oil driven transport from all over the world and powered by whichever lowest hydro bidder your miserly government is supporting this week is a bit much. The harder choice in the short term is to live with less, which no one is willing to do (that’s probably what’s driving hybrid/battery e-vehicle evangelism – a chance to bypass that choice).

I suspect that hydrogen fuel cells driving electrical motors are where we’ll go next in personal transportation (though why that’s only happening as a college project in motorcycling is a bit vexing). Fortunately, Honda is doing something on the four wheeled front. A super light weight hydrogen celled electrical vehicle bypasses the battery production nightmare, but then we aren’t moving toward light weight, minimalist vehicles. Would you want to drive a thousand pound hydrogen vehicle next to a massive SUV? That would be as dangerous as riding a motorcycle!

While that’s happening, advancements in nuclear engineering will hopefully drive us out into the solar system. The outer planets are a virtually unlimited store of non carbon based fusion energy, we just have to get there and collect the fuel (which is rare on Earth). If we took half of what we spend on military budgets world wide each year, we’d have an unlimited source of clean energy on tap within my lifetime. Instead we just keep doing what we’ve always done, stumbling forward in ignorance driven by greed instead of driving for real global advances in sustainable energy production.

Of course, none of that matters to personal transportation if we can’t find a better way to store electricity locally. Chemical batteries are an eighteenth Century solution to a twenty-first century problem. We really need to start advancing hydrogen fuel cells, kinetic storage and other non-chemical battery technologies. A near perfect scenario would be using d-He3 fusion to produce hydrogen with no carbon footprint. The hydrogen then works as an electrical generator in a fuel cell as it fuses with oxygen producing pure water.

|

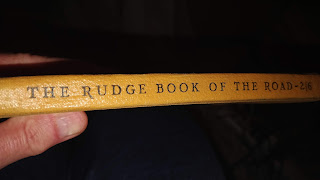

| A truly zero emissions vehicle with an abundant and powerful fuel supply? I’m dreaming of that future. |

I have no doubt that the internal combustion engine’s days are numbered and that the future is electrical. Companies like Zero Motorcycles and even EVs like the Nissan Leaf are doing their part to improve electrical engine efficiency, but depending on globally sourced, polluting chemical battery technologies isn’t the future. One day I’ll hop on my hydrogen fuel celled Zero Tsunami (because it produces only water, get it?) and zip off down the road knowing that I’m riding a vehicle that is truly sustainable.

Arguing between gasoline power and hybrid/EVs that depend on extremely polluting chemical battery technologies and fossil fuel driven electricity generation is like arguing whether your coal fed steam powered train is less polluting than my wood burning steam powered train – neither solve the problem, and one seems more about hiding it than fixing it.

***

Originally shared by Zero Motorcycles

Are motorcycles greener than cars? They are if you ride a Zero! Interesting discussion. Your thoughts?

Arguing on the internet, I should know better…

http://www.greencarreports.com/news/1105626_why-motorcycles-may-not-be-greener-than-cars-missing-emission-gear#comment-2845856393

I’m beginning to think that a few years ago a very smart MBA type walked into auto manufacturers and said the whole environmental thing can be resolved by moving the burning of fossil fuels out of sight of the general public.

The issue with climate change is that it’s obvious to consumers that they are responsible! Every time they put gas in the car they’re burning it. Simply move the carbon production out of sight and everything is good again, and you get a brave new legion of e-vehicle evangelists who will fight tooth and nail to ignore any evidence of this shift.

That your intermediate step is itself very environmentally damaging is easy to ignore. State that the batteries used in electric vehicles are very recyclable and everyone (especially your believers) will happily state that this is what is happening. Don’t demand laws that require recycling, don’t have any oversight over what happens to batteries when they’re done.

With carbon emissions and the pollution from the new systems that hide it happily out of sight, the general public can get their pride on riding around in hybrid and electric vehicles and never once see the damage they are doing first hand. Problem solved!