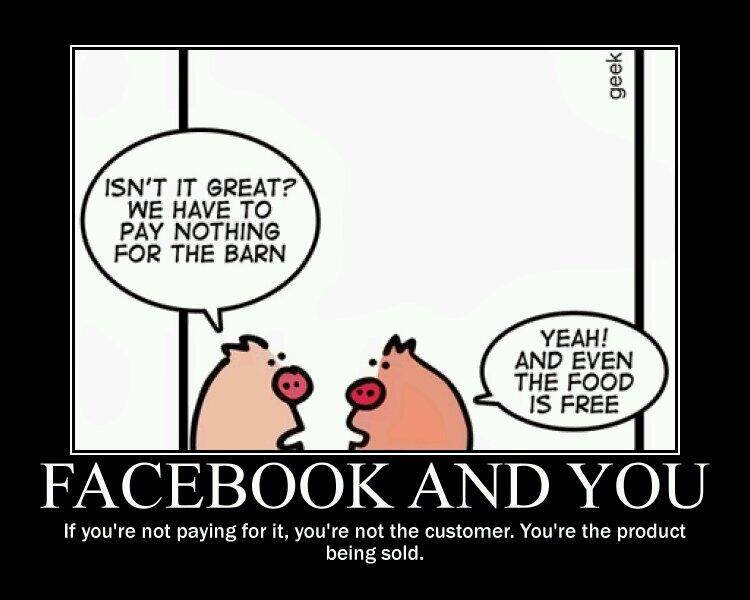

They showed this at the Google Summit a couple of weeks ago:

It’s a special kind of learned helplessness, and I see it every day when trying to get people moving on their computers again. There is nothing magical about computers, though many people like to think there is (it gives them an excuse not to engage in learning about them). If we’re going to make digital skills a foundational skill set in the twenty first century (and we certainly seem to be moving in that direction), then we need to integrate digiracy into curriculum in the same way we integrate literacy and numeracy, and we need teachers to be able to demonstrate competence in digital skill in the same way that we expect them to display proficiency in traditional literacies; acting helpless does nothing to move this forward.

Our board is about to take steps toward a BYOD/multi-platform approach to #edtech. This can’t happen until people get off the escalator and figure out how to open a book.

Helplessness, learned or otherwise, isn’t going to lead to the effective integration of technology in the classroom. How we train teachers to become digitally competent is a vital piece to this puzzle. The mini-lab approach with digital coaches assigned to their own tech-cloud is a way to encourage the tech-curious to develop better skills. It also (through collegial interaction with peers) lets the tech-curious spread their enthusiasm and know-how to the less keen.

| Build digeracy through scaffolded, objective learning with diverse technology. Opting out is no longer an option. It was an embarrassing approach ten years ago, it’s quickly becoming untenable now. |

That people seem to rewind well past where you think reasonable caution may lie in trouble shooting computers is frustrating from a tech’s point of view. If a user has a genuine issue with their computer, or something has actually broken, then we’re generally happy to be of assistance, but when a teacher says a printer is broken when it is simply unplugged, this points to a willful kind of ignorance. When that teacher is also one of the schools computer teachers I want to move to the arctic and give up.

A minimum expectation of digital fluency should be a willingness to address basic, operational issues before evoking support. If schools want to develop digital fluency, an expectation of honest engagement has to be where that starts. If the internet is really becoming that important, then it becomes incumbent upon the user to make that connection as stable and effective as possible. I’d say that 80% of the tech calls I deal with are people unplugging things they shouldn’t be touching in the first place, and then everyone else being too helpless to plug it back in again.

One of my grade 9s shared this as a video to help them out with an introduction to computers (the editing is hilarious): Komputer Kindergarten. MSDOS and the beige 1990s are the reason this sounds so antiquated (and funny). That so many people twenty years down the road still don’t “do that stuff'” is getting to be equally ridiculous. I’m not saying everyone has to be a technician, but everyone should be able to change their own tire, otherwise they shouldn’t be driving. You can’t be expected to operate the equipment effectively if you’re determined to know nothing about it and want nothing to do with it.

Effective teaching with digital tools begins with teachers, and I find so many of them not just reluctant but downright contrary to the idea of learning even the basics of how a computer or network functions. Some of that lies at the feet of teacher unions and school boards who have taught teachers to be helpless through locked, fear driven educational I.T. regimes. Educators who have bypassed these restrictions and developed digital fluency in spite of their union and board’s best efforts are the ones we need to bring back in from the cold now that the school technology cold war is over. Their fluency as digital coaches could create momentum to inflect enough colleagues to adopt a more open approach to learning technology.

The idiotic idea that technology is the realm of the young and if you want to know anything about it, just ask your students, needs to die. Students are the rocket scientists who unplug an ethernet cable to plug into their infected laptop so they can have faster internet. They then leave it unplugged and the next student comes along and instead of plugging the end back into the computer, plugs it into the wall, creating havoc as the network loops itself. Then everyone complains at how slow and unreliable the internet is; it’s not the internet that is slow and unreliable.

As school systems stumble along years behind business and society, they have finally gotten the idea that being online is just a new medium of communication (not bad, only a decade after the rest of us did). As education evolves into a more diverse, open technological environment, perhaps the hardest people to convince will be teachers who have bought into the fear and panic of their unions and employers and have been forced out of step with social expectation as a result.