One of the big shocks I got in philosophy was reading Bertrand Russell’s Analysis of Mind. If you can get through it you come to the startling realization that we are barely conscious at all. Russell does a thorough job of demystifying how our minds work.

|

With The Singularity looming a number of films attempt to

imagine what a super-human intelligence would look like. |

If you can imagine a being with the mental capacity to be constantly self-aware and conscious you begin to see just how different from us it would be. We have flashes of self awareness, moments of conscious consideration, but more often than not we fall back on instinct and autonomic processes. An always on intelligence would never surrender a decision to involuntary reflex, but we do it all the time. Basic processes aren’t the only thing at stake here. If you’ve ever found yourself in your driveway but unable to remember the drive home, you’re performing complex mental and physical processes without conscious thought.

That always on, aware intelligence is able to consider and respond in non-reflexive ways to all physical and mental challenges. Repetition is what we use to manage our limited ability to attend to the world around us. With sufficient muscle memory from repetitive action we are able to do pretty amazing things with our limited attention spans, but we have to offload cognitive capacity to our muscles and the world around us to achieve it.

The idea that we are dislocated minds that exist metaphysically is one of the last remnants of pre-Enlightenment thinking. From souls to Descartes’ ghost-in-the-machine, we’ve long cherished the idea that our selves exist beyond the mundane world in which we find ourselves. But the very idea of a self only happens because it is situated in reality. Context, rather than self awareness, is what gives us the continuity required to acquire a sense of self. Your ‘youness’ isn’t a magical property that exists in the ether, it’s a consequence of your mind interacting with the world around you. The circumstances you find yourself in are created by past action. People around you treat you as they do because of past action. What you think of as your mind is actually a series of circumstance that expand beyond your head and through your body into the world around you.

A skilled person recognizes this process and ‘jigs‘ their environment, using their surroundings to support their work. You see this in everything from a scientist’s lab to a short-order cook’s kitchen, to a teacher’s classroom; they all design their work environment to allow them to do their jobs better (assuming they are good at what they do – jigging an environment to perform well is a sign of mastery). In extremely performance focused jobs, like professional sports or acting, this jigging takes on talismanic power that look like superstitions to the uninitiated. Our psychology can be very sensitive to how immediate surroundings support or detract from our performance. The pre-game ritual of an athlete before a game or the actor before going on stage both reflect this. Our intelligence leaks out into the world, forming it to our will in order to get ‘our heads on straight’.

|

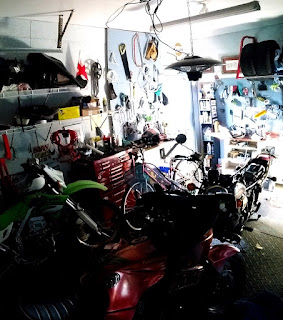

| I take the concept of jigging my work space very seriously. |

Jigging of their environment is a window into student learning. You can see how thoroughly a student understands a process by how well they manipulate their environment. The student who can’t find the right tool for the job probably doesn’t understand the job very well. My father always used to give me a hard time for leaving his workshop in a mess; I get it now. If you can’t find a tool when you’re in the middle of a complex task you won’t be able to perform the task well. Your continuity of thought is broken by poor workplace planning. My father’s assessment of the dirty shop was actually an assessment of my understanding of the craft of the mechanic.

|

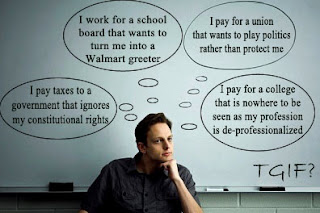

True mastery learning requires an advanced practitioner to

jig their working environment to produce complex work.

This isn’t that. |

The stock classroom is a Cartesian throwback to the disassociated minds myth: our minds are magical buckets which we can fill with information. Of course they aren’t, they are fractured, non-continual biological processes designed to interact with the world around them. A human mind only blossoms in the presence of an interactive reality. You have to shed the myth of a Cartesian mind in order to see the absurdity of the typical classroom.

If education is going to adapt to this simple truth it needs to recognize that learning isn’t confined to mental processes. Even cognitively focused courses of study like mathematics are recognizing that tangible representation improves student learning. If you teach students like brains in boxes you don’t get very far.

Recognizing tangibles in teaching concepts is only the first part of this incorporation of an accurate philosophy of mind in learning. The real power comes in creating adaptable learning environments that encourage student control. If you’re teaching anything sufficiently complicated then allowing students control of their learning environment will only improve their chances of mastery. If they can’t control their work space (or worse, it’s handed to them complete), they are being robbed of the opportunity to own their learning. Environmental control also allows teachers a vital insight into how well a student understands the material they are learning. If a student designs a non-functioning work space it shows you just how far from understanding the basic concepts of what they’re trying to do they are. It is a common occurrence for the least capable students to walk up to me days before the end of a two week engineering project and tell me they are missing key components to finish it. This is a valuable insight for both myself and the student into just how ignorant they are. The worst thing we can do is what we do now: put students in institutionally designed spaces that demand conformity and tell them to do it in their heads. A key aspect of mastery learning is recognizing how expertise is rendered in the world around us, and then using that information to assess understanding and improve learning.

NOTES

Bertrand Russell, On Mind

Finishing off Descartes’ ghosts

Rene Descartes, ghost in the machine

If we can’t have souls, we can have magical, metaphysical minds!

Matt Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head

A modern dismantling of Enlightenment ideology that has run wild

I recently attended Stratford’s Possible Worlds.

It plays on a conceit that you see in a lot of drama (Jacob’s Ladder, Inception, The Matrix), that we would be incapable of realizing that the world around us isn’t real. This conceit trivializes reality and sends us back into that superstitious state of magical minds.

I’d argue that our existence actually precedes and produces our intelligence. We wouldn’t be what we are if we were brains in boxes being fed information; reality defines our intelligence. I had a lot of trouble getting into Possible Worlds because it used science and tech babble to lead the audience through a fractured dreamscape, depending on our belief in magical minds to suspend our disbelief.