Our school is the only local high school in the area. If students want Catholic or special education, they get on a school bus for over an hour a day of commuting down to Guelph. I’m a big fan of choice so, while I think it mad, I don’t have much to say about a student who wants to spend over 194 hours a year (that’s over 8 full days of riding 24 hours a day) on a bus to Guelph and back for specialized education, as long as it’s a choice they’ve made.

|

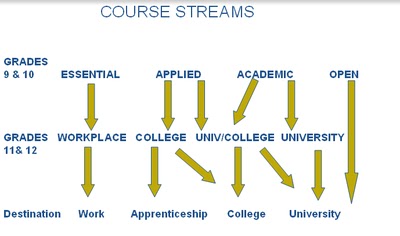

| Ontario’s high school streams seem pretty straightforward, they are anything but in practice. |

Our public board think it wise to ship our essential level students down to Guelph for special education. This isn’t a choice, it’s a system driven process. The Guelph school for this doesn’t fill up with locals so the surrounding community schools are expected to ship their most at-need students out of their home communities every day. This is an ongoing pressure in our community.

At our recent heads’ meeting there seemed to be support for the idea of our school being a comprehensive, community school that serves everyone, but we struggle to run essential sections because parents resist putting their children into it, the board doesn’t section us to run smaller essential classes and many teachers in our school would rather be teaching academic students. It’s an uphill struggle to create a comprehensive local school that supports everyone in our community.

Because we aren’t sectioned for essential classes (those smaller sections are given to the specialist school in Guelph), we end up populating applied level classes with essential students. It is so difficult to align parent perception, board support and student ability that we place all non-academic students into the same room. This is where the proliferation of fifties comes in.

A teacher in our school recently said, and in retrospect I agree, that we place essential students into applied classes and lower course expectations to accommodate them. This not only does the essential students no favours, it also dilutes applied curriculum goals.

The people running the education system tend to be successful professional educationalists; very experienced with the system having spent little time outside it. These educators see kindred spirits in academically streamed students who are successful in school and make effective use of the system. These teachers want to teach students like themselves. Asking them to work with students who find school a challenging environment or aren’t on the same academic trajectory they experienced is difficult for them.

The predisposition of teachers makes academic curriculum somewhat sacred, but applied classes aren’t. Applied students should be on apprenticeship and college skilled labour tracks that demand hands on (applied?) skills. While less theoretical in approach, applied classes are supposed to be rigorously skills focused. When you put students who lack basic literacy and numeracy into a grade 10 applied class you make grade appropriate learning nearly impossible.

How do teachers manage this? If you fail a student, you get called into promotion meetings at the end of the semester where the grade you’ve given becomes the starting point for an inflationary process that floats fails up to passes. The best way to avoid this is to simply award a 50%. What is a fifty when it’s really a 42? At its best, a fifty means a student has not reached minimal expectations for a class. Would you want the mechanic working on your brakes to have gotten there with fifties?

The teacher I was talking to suggested that the number of fifties being handed out has mushroomed in the past few years. Those statistics aren’t made available to us because they would make a travesty of curriculum expectations, but I suspect he is right. A fifty means the government gets to say graduation rates are up. A fifty means the ride ends at graduation because no secondary program would accept a student with a D average. A fifty means you’re not sitting in promotion meetings watching your semester of careful assessment being swept away to support policy.

The range of student skill in my classes is astonishing. My current grade 9 classes range from students who could comfortable complete grade 11 computer engineering curriculum next to students who appear unable to read, yet I’m supposed to address that range of skills in a 50-100% range in a single course.

Perhaps we will find a way to reintegrate Ontario’s carefully designed secondary school streaming system, but considering the various pressures on it in our area, it’s going to be an uphill struggle.

NOTE

Re: school busing children…

Time isn’t the only resource being spent. School buses get 6-8mpg, Guelph is about 15 miles away. A (very conservative) 30 mile round trip (it’s much higher if you want to consider all the pickups and drop-offs) is a (very conservative) 15 litres per day of diesel (probably double that for your typical start/stop run), per bus, and we have a number of buses making that trip 194 days per year.

Someone better than I can calculate the overall environmental impact (how many other vehicles are also held up burning fuel while these buses grind down to and back from Guelph every day?). Making an economic (let alone moral) argument for shipping our essential students out of their home communities seems impossible.