Originally published October, 2013 on Dusty World.

I’m currently teaching two grade nine classes of introduction to computers and coaching the senior boys soccer team. In both situations I’m trying to understand and develop their response to failure. This is something we’re singularly bad at in education. Instead of developing resilience around failure we try to mitigate failure entirely.

The soccer team has shown such a lack of resilience that they are essentially in tatters. When given opportunities to recover from failure they have responded with dishonesty, poor sportsmanship and a lack of character. Continually trying to coax them into right action has been exhausting and ultimately a failure on my part as a coach which I find very distressing. There is a culture on this team that I’m finding impossible to overcome.

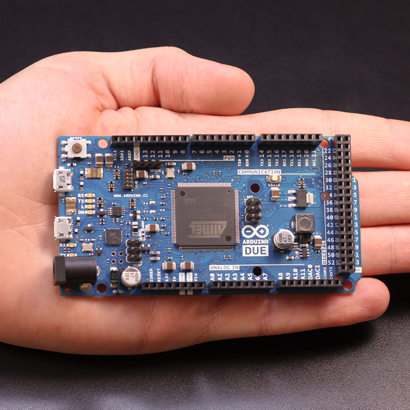

The grade nines, while tackling Arduino for the first time, are also running into failure though they are handling it much better than the soccer team. When they realize that they won’t be made to suffer for failure (this involves overcoming years of training by our education system), they begin to play with the material in a meaningful and constructive way. Removing fear of failure from the equation has been successful in both classes and the confidence that results is based on real, hands-on, experiential learning.

| http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.04/genX.html |

So much of what we do in a classroom is artificial. Artificial challenges in an artificial environment producing artificial assessments while working on artificial timelines. The same can be said of those epic wins players think they own in video games.

This brought me back to an article I read in WIRED a long time ago called Generation Xbox wherein they talked about the culture of gaming in such a forthright way that it stuck with me. Anyone who has been teaching kids in the last ten years will see a lot of truth in these observations.

One of the reasons gamification has connected with education so comfortably is that the two things deal in artificialities. Both focus on engagement and subvert realism in order to ensure continued attention. Being in a classroom is much like being in a game complete with rules to follow and points to be scored. We grade students in much the same way that a game gives out points – we award players for willingly submitting themselves to the rules of the game; submission is a prerequisite for victory and victory is given rather than taken.

When you win in a video game or in a classroom you aren’t experiencing success in a real way. It is an artificial environment designed to breed success, you are in a place designed by committee to appeal to the widest range of people. The attention and engagement of the student/player is the goal, everything else is in support of it. Yet people develop very real senses of themselves around these false victories. Our self image is molded around what we think we’re good at and many digital natives consider themselves masters of the universe because they have played games successfully. Many academics believe that they are masters of the universe because they were able to submit to education successfully.

If social constructs like games or education or economics are designed to focus entirely on inclusive engagement then the result is a population with no ability to think outside of these social constructs. They don’t develop meaningful meta-cognition or resiliency. When you’ve been beaten badly it shows you something about yourself. When you’ve been beaten badly it knocks you out of habitual response and into a new and potentially more successful means of overcoming your failure. In that scenario even a less painful loss could be seen as an improvement, but we are doing all we can to remove pain from everything.

One of the reasons gamers migrate to multi-player versus games is because you can test your ability against someone who isn’t a benign agent of the game’s mediocrity engine. As in sports you are able to test yourself against your peers. You can bet that the human being on the other side won’t bell-curve their play to suit your level. That’s how you end up with 9-1 soccer games, or getting pwned online. It’s in these extremes that gamer culture and sports seem most alien to educators. It’s in these extremes that my soccer players have nothing in their vocabulary to respond honestly and constructively to failure.

When starting the circuit building unit in computer studies the grade nines were overwhelmed by something completely new to them. I gave them detailed instruction and support but would not do it for them. I did stress that if they weren’t paying attention to what they were doing they would find this impossible and when one would ask for help while simultaneously looking at their smartphone or with an error I’d already helped them with once I’d walk away. Circuit building wouldn’t bell-curve for the class, it wouldn’t simplify things to make it easier if students didn’t get it. They had to respond to reality and reality wasn’t interested in making it easier.

At one point a colleague from the English department wandered in and watched them working on their circuit building for a few minutes. He said, “it’s nice to be in a classroom where the students are actually doing something.” then, after a pause he added, “you really don’t have to worry about engaging them do you? They’re all right into it…” Reality can do that to people, it’s a genuine challenge. My job as a teacher is to give them the time and materials to figure it out for themselves.

If you’re excited about gamification then you’re excited about what is simply a new layer of artificiality around an already artificial situation. Not everyone should see success in every endeavor. It’s good for you to fail every once in a while, it makes you more compassionate, humble, creative and self aware; all areas I see the digital native struggle with because their virtual wins have more to do with entertainment than they do with reality.

If you’ve seen success in a system designed to provide it you’ve got to question the value of that success. If you want to earn success look for a challenge that wasn’t designed by committee mainly to keep you engaged. Whenever what you’re doing has engagement at its heart you’ll find the victory to be false because it was designed to ensure it for you in order to keep you playing.