The idea that technology will somehow make teaching easier (or superfluous) makes me sad… and angry. The idea that it might be making us inferior to previous generations drives me right over the edge.

I’ve been reading Nick Carr’s The Shallows. If you’re a techie-educator, you might disagree with him, but the Pulitzer prize panel didn’t. Neither did the Laptops & Learning research which demonstrated that students retain less information about a lecture when they have a digital distraction on their laps. Carr’s argument that digital tools teach a plastic brain to reorganize in simplistic ways has resonated with many people, usually people that didn’t like digital options in the first place.

There is a big backlash against this single minded approach, which I think was addressed at the recent ECOO conference. If students aren’t able to recall details from a lecture, I think I have to start with the sage and the stage. The idea of passive learning is rapidly losing traction as the most effective way to teach. Countries that cling to the idea (usually as a cost saving measure and to try and adhere to standardized tests) are tumbling down world rankings in education.

A teacher who talks at their students for an hour will view laptops in their class as an invader who fights them for their (not so) captive audience’s attention. If you want to accept digital tools into a uni-directional, passive classroom environment, they are going to disrupt the learning.

Several of my students came up to me today and asked me how to perform a function in imovie (we’re editing videos we’ve been working on for three weeks). I told them both that I wouldn’t show them. Following the sage logic, I should have given them an in-depth 20 minute lecture on how to add pictures to credits, and then chastised them if their attention ever seemed to wander to the imacs in front of them. Instead, I suggested they look at the help information, and then go out into the wild west of the internet if they were still lost. I not only wanted them to resolve their own (relatively simple) learning dilemmas, I wanted them to feel like they had solved them themselves. Within ten minutes they both had figured out what to do without being spoon fed the details; they owned that information. For the rest of the period they were showing other interested parties how to do it.

If I had saged that whole thing, digital tools would have appeared to be a detriment to thinking and learning; nothing but a distraction.

The other side of this is the idea that teachers no longer teach, they simply facilitate, like trainers on a bench. This usually plays to the ‘technology will make my life simple’ crowd, and it isn’t remotely true. To begin with, many students haven’t learned to use digital tools in productive ways. When they turn on a computer it means hours of mindless, narcissistic navel gazing on Facebook. Students in my class are expected to use the computer as a source of information, a communication tool and a vehicle for artistic expression. They aren’t going to be the players if they don’t even know the game. I have to model and learn along side them, I have to demonstrate expertise on the equipment, and more importantly, expertise as an effective, self-directed learner. If I do this well enough, I can eventually step back, but I’m more the weathered veteran on the bench good for a few more pinch shifts when I’m really needed, than I am a towel jockey.

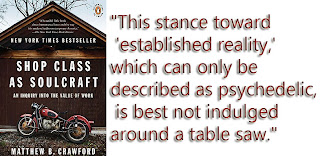

A good teacher challenges, and then is able to recede, but even that recession is a carefully modulated choice that balances student ability with student independence. This is never going to be anything but a challenging dance that you will always be leading, even if you’re not necessarily in front. We CANNOT assume that students know how to use digital tools effectively, any more than we can assume they will intuitively grasp band-saws, or nail guns.

If you’re into tech in education because you think it’s an easy way out, it’s time to realize that there are no short cuts, and that your job will constantly change, and you better be mentally lithe enough to keep up with it, or else the digital natives will use the tech in the most simplistic, asinine ways imaginable, and Nick Carr’s Shallows will become the truth.

In schools we create artificial learning environments for our children that they know to be contrived and undeserving of their full attention and engagement… Without the opportunity to learn through the hands, the world remains abstract and distant, and the passions for learning will not be engaged – Doug Stowe (

In schools we create artificial learning environments for our children that they know to be contrived and undeserving of their full attention and engagement… Without the opportunity to learn through the hands, the world remains abstract and distant, and the passions for learning will not be engaged – Doug Stowe (

profession. The blog led to presentations at Edcamps, conferences and PD. It’ll lead to a book at some point me-thinks.

profession. The blog led to presentations at Edcamps, conferences and PD. It’ll lead to a book at some point me-thinks.