Last year while at the CyberTitan National Finals in Fredericton I happened to be standing by Sandra Saric, ICTC’s VP of talent innovation, during a photo opportunity where the fifty or so student competitors were all together on a long stairway. Under her breath she wondered, “where are all the girls?” There were maybe three or four female contestants. Sandra’s comment resonated with me and I became determined to put together a female team that would get their own points and where no one is ‘just a sub’.

Last year while at the CyberTitan National Finals in Fredericton I happened to be standing by Sandra Saric, ICTC’s VP of talent innovation, during a photo opportunity where the fifty or so student competitors were all together on a long stairway. Under her breath she wondered, “where are all the girls?” There were maybe three or four female contestants. Sandra’s comment resonated with me and I became determined to put together a female team that would get their own points and where no one is ‘just a sub’.

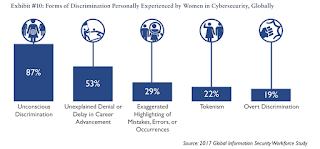

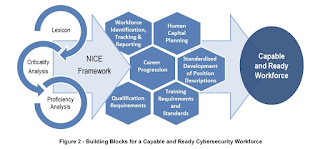

CyberTitan and Cyberpatriot have doubled down on this focus on bringing women into a cybersecurity industry that has only moved from 11% to 20% female participation in the past five years. For the 2018-19 season any all-female teams had their costs waived. For a program that isn’t rolling in support, that made a big difference and enabled me to pursue this inequity.

Graduating girls into non-traditional careers is an ongoing challenge in education. Pushing against social norms is never easy, particularly so in our conservative, rural school where gender expectations tend to be even more binary and specialized program support significantly lower than in urban environments. I’ve managed to have one or two graduating female computer technology focused students each year, but even that small step has only come after massive effort, and it’s not nearly enough. Even with all that stacked against us, we still managed a 33% female participation rate in CyberTitan this year, and of our six Skills Ontario competitors, two were female. We’re aiming to raise that even higher next year.

This year CyberTitan made a point of trying to address the very one sided gender participation in the cybersecurity industry by making the national wildcard position open to all-female teams. There were only 15 out of 190+ teams in the competition, and our Terabytches finished in top spot. We were delighted to discover that one of our boy’s teams actually finished one place out of the top four eastern teams. A number of people (oddly all male) grumbled about the all-female wildcard spot, but the irony is that we knocked ourselves out of the finals.

Taking an all-female team meant that I needed a female chaperone with us. Fortunately, our board’s head of dual credit programming is a triple threat. Not only is she very tech focused (her student just won top secondary brick layer in Ontario!), but she’s also computer science qualified and an absolute joy to travel with (I went to Skills Canada Nationals in Edmonton with her last year), so I quickly asked her to join us when the call came through to bring our girls to nationals. Not only did she not need coverage herself, but she kindly covered mine so my school literally paid nothing for this trip.

I like to think I’m pretty sensitive to gender roles in the first place, but taking an all-female crew to this event had me constantly seeing micro-aggressions I might have otherwise missed. Within five minutes of picking up the Toronto (all-male) teams on the bus ride to Ottawa, one of them had intimated that we were only there because we’re a girl’s team. Another later said that it’s not fair that girls are getting special attention. It must be tough when everything isn’t about you all the time. These comments were a daily occurrence from all the other teams, even the two co-ed ones, one of the girls of which said that she was just the sub.

That same Toronto team was able to attentively listen to a male speaker during the visits to cybersecurity companies in the Ottawa area after the competition, but the moment a woman stepped up to speak they began a loud and rude conversation among themselves. I wonder how often these little princes (who did ever so well in the competition) have had their gender superiority enforced to develop such outstanding habits.

Walking in to the competition, our team had all signed in but one and as she reached for the pen a boy from another team stepped in front of her like she wasn’t there. Talking to Joanne and the team about it after, they shrugged and said, “you get used to it.” By that point I’d been triggered by this so much that my already light grip on my aspie-ness was slipping and I was starting to get right angry, but even that anger response is couched in a male sense of privilege. When a man gets angry it’s seen as assertiveness, when a woman gets angry she’s a bitch, which brings up yet another point.

After fighting to get a team together against overwhelmingly genderized expectations in our community, and encouraging that team to develop a representative sense of identity in an overwhelmingly male contest, and then having to push back when the powers that be didn’t like the name, you’d think this was all starting to get too heavy, but it has only clarified my sense of purpose.

After fighting to get a team together against overwhelmingly genderized expectations in our community, and encouraging that team to develop a representative sense of identity in an overwhelmingly male contest, and then having to push back when the powers that be didn’t like the name, you’d think this was all starting to get too heavy, but it has only clarified my sense of purpose.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if girls didn’t have to get used to being invisible and could self-identify without being told what they can and cannot be called? Wouldn’t it be wonderful if everyone could be what they are and explore what they could be without some small minded traditionalist trying to put them in a superficial box? When you push back against that social apathy you get a surprising amount of kickback from the people it benefits. Ontario’s current political mess is entirely a result of that conservative push back.

You even get kick back from the people it subjugates. At an ICT teacher’s meeting earlier in the year, a teacher from an Ottawa school said she would never run an all female team because it isn’t fair to her boys. Were everything else level, I’d agree with her sentiment, but in the landslide of unfairness around us, you’d have to be wilfully blind to ignore historically integrated misogyny in order to be ‘fair to your boys’. This teacher taught at the local International Baccalaureate school, which brings up yet another side of competition and privilege.

| Toronto, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Vancouver… Fergus. Your usual expected centres of digital excellence. |

We’re a rural composite school that spreads itself thin catering to our entire community. The major industry in our region is farming, we recently had our annual Tractor Day. Our school contains programs for developmentally delayed students and has a sizable special needs student population. We also manage to run a number of successful academic programs, but these are by no means our sole purpose. Tech exists in there somewhere.

As far as computer technology goes, our lab is a room full of ewaste we’ve re-purposed to teach ourselves technology. Thanks to some board SHSM funding and an industry donation from AMD we got the cheapest CPUs and motherboards we could find and put them in ten year old ewasted board PC cases running on ancient hard drives and power supplies. My students have never touched a new keyboard or mouse in our lab. We have to clear away our practice networks built of garbage because we have the largest tech classes in our board and province and we have no room in the lab to leave those networks set up with classes of 31 coming in next period. I don’t imagine any of the other schools operate in a similar environment.

We returned the board desktops in our room to the school who redistributed that money into other departments because you can’t teach digital skills on a locked down machine. We’ve received no school funding for the current lab. Looking into the backgrounds of who we were up against in this competition, every other school is a specialist school from an urban centre. In many cases they only teach top academic stream students pulled from other schools, and yet they can’t put together an all-female team for this competition? One wonders if those competition focused, talent skimming schools inherently encourage gender imbalanced technology with their incessant focus on winning.

|

| We’re built on sweat and tears. Our disadvantage is also our strength, but when it comes to competition it gets frustrating not getting to run the same race as everyone else. |

The socio-economic side of privilege is every bit as battering as the sexism. One of the little princes from Toronto was telling a Terabytche about his parent free March Break touring Europe with his friends. She replied, “Hmm, I spent the week playing video games in Fergus…” Last year half of our CyberTitan team had never left Ontario before, let alone had a week in Europe with their buddies. The students who attend these specialized schools tend to come from economically enabled backgrounds and have parents looking to leverage that advantage. The amount of support those wealthy families rain down on these specialty programs is yet another advantage we can only dream of.

Think the privilege ends there? Because we cater to the full spectrum of students in our community, my classes are huge in order to reserve smaller sections for high-needs students (even though many of them also take my courses). In talking to other coaches, my class sizes were the largest by a range of 20% to a staggering 50%, and their operational budgets ranged from five to twenty times what mine are; I teach up to a third more students with a fraction of the budget in a lab made out of garbage.

We were surprised to learn that we would be beginning the competition short-handed because one of the IB schools had exams some of their competitors had to write, so to keep it fair we’d all start short handed. Right. Gotta keep it fair.

That these urban, wealthy, gender empowered, privileged kids are flexing that privilege doesn’t surprise me. That they continually complained about special treatment for a group of underfunded, rural, girls busting through gender expectations in technology, and who fought their way to these nationals literally using ewaste, only underlines the expectation that comes with their privilege; the expectation of winning.

In spite of these society-deep gender inequities and our specific socio-economic circumstances, the quality of my students continues to shine through. Finishing fifth last year with only four team members and two broken competition laptops was just the kind of awesomeness I’ve come to expect from our kids. It didn’t occur to me to have the whole competition changed to make it fair for them.

This year we managed a ninth place finish out of ten teams, only beating the intermediate team who can’t really compete with older more experienced teams anyway. That earned another round of, ‘you’re only here because you’re girls’ from other teams. After careful consideration I think my response is: if you came from where we came from, I wonder where you would have finished.

Is winning more about how you perform, or how you are economically and socially engineered to succeed? I’d love to give gender and social equity to those complaining about our presence. Having those boys experience people talking over them and stepping in front of them like they aren’t there would be good for them. Facing down gender based prejudice in an industry where women are a small minority is an act of bravery, not special treatment. Wouldn’t it be nice to bring everyone up instead of holding people down? To do that we need to recognize what winning is and how privilege enables it.

Next year we have returning students for the first time in this competition. I’m aiming to put a co-ed team of our fiercest veteran cyber-ninjas together, build tech out of garbage and then win anyway. Nothing gets me going more than an underdog fight against privilege, especially when those with that privilege like to selectively ignore it.

I hope we’ll be back with another all-female team too. Many of the Terabytches are interested in returning, but I can understand their hesitancy. Working through this competition has challenged many of them in ways that were unintended. If it was just about technical skill, then we’d have been much further down the track, but when you have to fight to be noticed and are constantly talked down to, it’s exhausting. I get why they might think twice about going through the never-ending online and face to face sexism all over again. It’d be nice if other schools would pick this up and run with it instead of rolling their eyes at it.

Last year was all about giving the haves a black eye, and it thrilled me. We didn’t return home with a trophy or a banner, but we were running a different race. I’m not even sure how anyone could make this an even race. Teaching technology is dependent upon access to it, and the digital divide is deep and wide. This year it was about something even bigger. Yet again we came home empty handed, but I think what we won was worth more than any of the prizes. I hope the girls see that and come back to defend their title.

|

| An amazing opportunity and a chance to begin to create balance in an industry that lacks it. Great work ICTC! |

from Blogger http://bit.ly/2Qf7aA5

via IFTTT