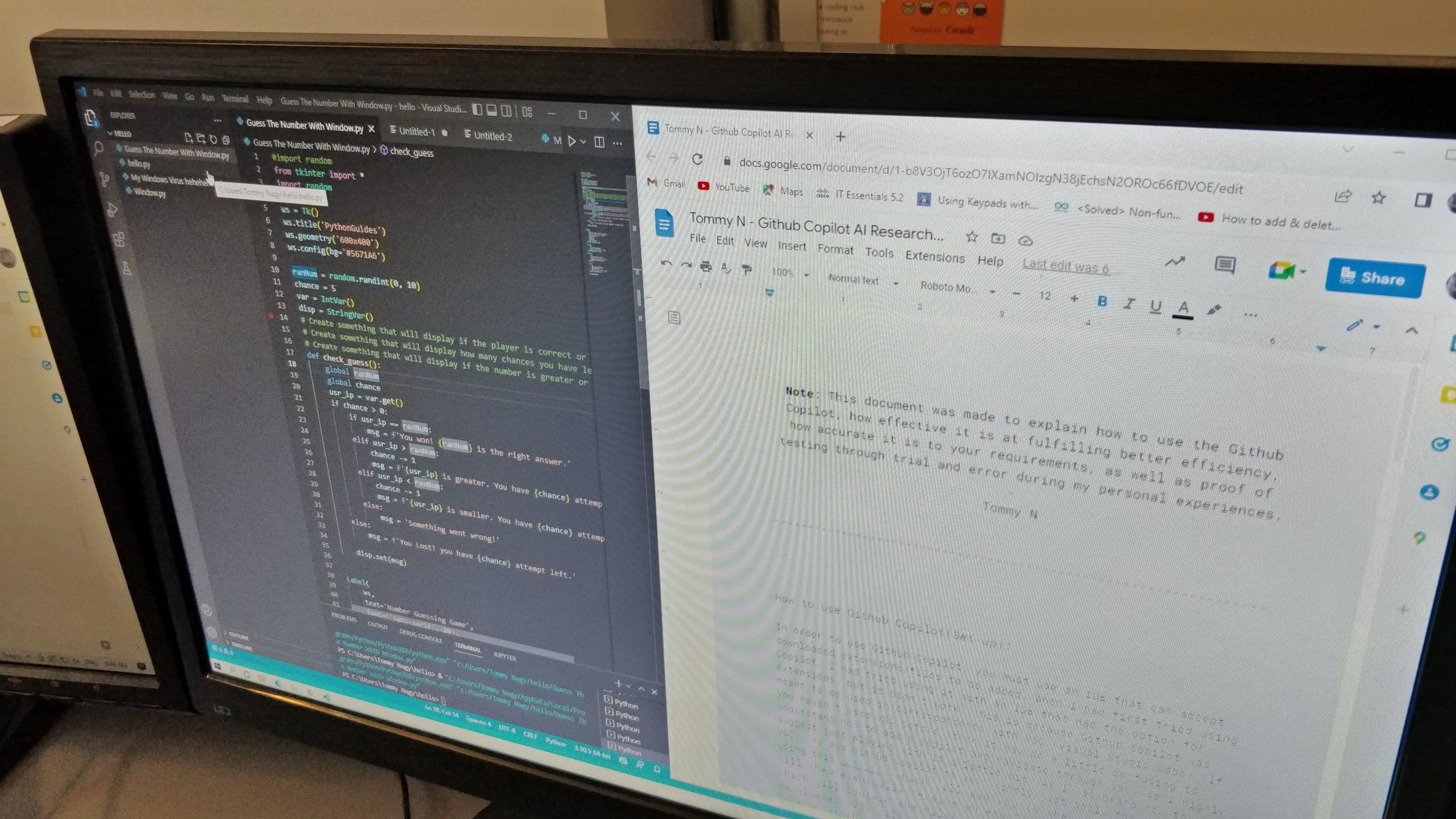

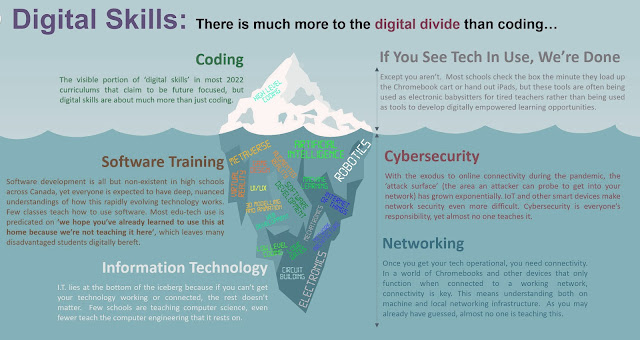

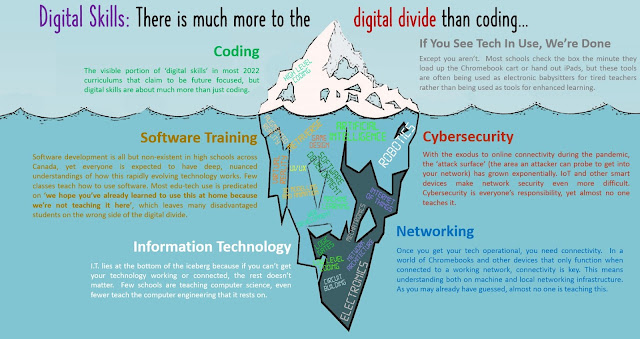

I’m currently working with partners developing curriculum that creates an understanding of how computers work. The challenge is in getting adult focused instructional designers to recognize the enormous gaps students have in terms of their understanding of computer technology. Digitally fluent adults assume young people have an intuitive understanding of how these machines work, but they don’t. If you assume this you end up with frustrated and confused students.

We rolled back initial lessons to the point where we’re introducing students to how computers store local files, but even that wasn’t far enough. With no coherent digital skills curriculum in our schools, you have to clear away a lot of misconceptions and back up the truck all the way before you can start building a coherent understanding of how digital technology works. As in the case of most problems, thinking about pizza helps…

Only Old People Use Computers…

‘Wait a minute!’ you say. ‘I’m super cool! I don’t use old fashioned things like computers! I’m a digital native who lives on their phone.’

Newsflash! Smartphones are computers! So are tablets, Chromebooks, laptops, desktops, IoT devices like your smart thermostat or the Alexa that’s listening all the time. Because they’re all fundamentally the same thing, you can understand and fix them when they go wrong. You’re using a computer to read this right now, it just might not look like one.

ALL COMPUTERS ARE LIKE A PIZZA

If you think about pizza when you’re diagnosing a computer (which might look like a phone, car fuel injection system, laptop or smart fridge), it helps you to isolate where the problem is and clarifies what you need to do to fix it. All electronic computers share the same fundamental components, and those components are pizza-licious!

The Dough: HARDWARE

This is the part of the pizza that can look very different. The physical shell we put a computer in can range in size from a smartwatch to building-sized supercomputers. Generally, the smaller they are the slower they are because electronic computing generates heat and that’s hard to get rid of when you can’t install fans and other cooling stuff to get the heat out and let the processor run at top speed.

That’s why desktops always feel faster than laptops. Their architecture can be designed for speed because engineers can get rid of the heat made from running a processor fast. Mobile processors are often throttled down desktop hardware. Even smaller computers tend to be specialists only having to do a few tasks that engineers can optimize the hardware for. Phones can only run certain apps, watches are even more limited and single function computers like ATMs or smart thermostats can optimize all of their hardware to a single task.

If you’re having hardware headaches, like a computer overheating and locking up, you can fix it like a mechanic, with tools (and thermal paste) and some physical attention. If you get handy enough, you can even start building your own crusts.

The Sauce: FIRMWARE

Computer hardware doesn’t know what it is – it’s just STUFF. When you first power up a computer (phone, desktop whatever), you often see text appear for a second and then disappear. That’s the saucy FIRMWARE. Firmware is software that’s written onto a chip in the computer that tells it what kind of hardware its running on.

Firmware is sometimes called BIOS, which stands for Basic Input/Output System – which is literally what it is; software that tells the computer what hardware it has that takes care of inputting and outputting data. UEFI replaced BIOS on modern computers, but it’s just a fancy BIOS with graphics that make it easier to navigate. It’s pointless acronym expansion like this that puts people off learning about computers!

The Cheese: OPERATING SYSTEMS

On top of the firmware sauce you have the cheesy OPERATING SYSTEM. You’ve seen logos for them for years, but probably don’t give them much thought. If you’re a PC type person you’ll have seen Windows evolve through XP, 7. 8. 10 and now Windows 11 versions. Apple people know OSx (Operating System 10), and if you know any nerds they’ll tell you about Linux – the free, open source operating system that gives you great power to modify.

OSes are the software that span the gap between users and the machine itself. OSes have a lot of work to do running an incredible variety of applications, some of it very poorly made, without crashing, though sometimes they do. OSes have to integrate all the different input methods (touchscreen, mouse, trackpad, keyboard, etc) and all the possible output methods like screens, printers, haptic feedback or even the LED lights on the computer itself. Juggling all of that hardware and software, all of it engineered to different standards and coded with varying levels of skill, is a might task, though that doesn’t stop people from ripping on the cheesy OS…

It’s in the cheese of operating systems where you run into a lot of headaches, unless you make a computer so absurdly simple that it can only do one thing. Rather than learn the complexity computers are capable of in order to leverage the flexibility that a general purpose machine can perform, we’ve surged toward simplicity. It started with Apple’s ‘walled garden’ approach to iOS, where apps must comply with (and pay for) strict standards. This allowed the iPhone to create a larger user base because it simply worked – just not in as many ways as it might.

Android came along with a more open approach and took back some market share, but most people would rather do less if it means not having to learn anything about computers. Nowhere is this better shown than with Chromebooks. Chrome OS that runs on a Chromebook is actually a flavour of Linux designed to give you only a browser. They’re great because you can barely do anything with them and they’re easy to manage – which is why we use them in schools to teach digital fluency.

Of course, if you’re crafty you can work around all these blocks. You can ‘jail break‘ Android and iOS phones to allow you to update the OS (many companies freeze you out of updates after a couple of years in order to force you to buy a new device). Jail breaking usually involves finding a hacked firmware (remember the sauce?) that has removed any locks on what kind of OS can be installed. You overwrite the official firmware with deristricted firmware sauce and then you can keep updating your Android or iOS versions or install software on the device that the manufacturer blocked.

The Toppings: APPLICATIONS and PROGRAMS

A pizza wouldn’t be a pizza without some toppings that customize it to your taste. When you first start up a new computer it’s a plain cheese pizza. Your dough (hardware) powers up and runs your sauce (firmware), which makes the computer aware of its hardware and then hands it all off to the cheese (operating system), which loads you into a plain pizza starting environment.

If you’ve got any problems that prevent you from getting to your OS starting screen then you know where to look in the boot process to solve the problem. If the machine doesn’t power up, you’ll be working with the dough. If it powers up but gets stuck in a text screen before the OS logo appears, you’re focusing on the sauce. If the OS logo appears but you don’t get to the start screen, you’re fixing the cheese.

As you customize your pizza computer to your needs, you install apps adding another layer of complexity to your poor old operating system. Generally, the longer a computer has been with a user, the more toppings they’ve piled on. This gets complicated by apps and operating systems getting out of date, then you might have rotten toppings wrecking your otherwise yummy pizza. You’ve got to keep your toppings (OS cheese and even your FIRMWARE sauce) up to date or you can end up with problems. The vast majority of pizza lovers aren’t very good at looking after their cheese wheels, which makes hackers very happy.

If you really like pizza, you’ll make your own…

These PC pizzas were just coming into being when I was growing up in the 1980s. Early machines came complete as a ‘deluxe pizza’ with the crust, sauce and cheese all per-selected for me. My first two PCs, a Commodore VIC-20 and Commodore 64, offered crust upgrades (memory I could plug into the expansion port), and gave me control of the toppings, which we quickly learned how to customize.

In the late 80s/early 90s I got into i386 IBM clone computers. This was my first go at a truly DIY pizza PC. I got to select components to customize my crust, the sauce firmware comes with the hardware, but then I could pick my OS cheese too. I haven’t owned a ‘deluxe’ pre-made pizza PC since. My current desktop is a custom case I selected for its big fans so that it runs quick, cool and quiet (it also happens to look like the bat mobile). To that I added a high-speed motherboard, fast processor and lots of RAM (fast memory), so it never hesitates, even when I’m running many applications at once. A VR ready video card means my graphics are super quick and the whole thing is aimed at precisely what I want to do with it. Custom crusts are the way to go.

For the cheese I always install multiple operating systems. Right after my firmware sauce finishes it gives me a menu that lets me choose between many different OS cheeses depending on what I want to do. My desktop will boot into two versions of Windows, three versions of LInux (each customized for a specific task) and it even ‘hackintoshes‘ if I need to test something in an Apple environment. My pizzaPC changes its cheese based on what I need it to do!

The Pre-made Pizza Dilemma: DELUXE PIZZAS USUALLY AREN’T

The urge to Chromebook us has always been with us. The ‘game system’ industry is a Chromebook for games.

Pre-selected crust, sauce and cheese lead to a limited selection of

toppings (games), but this simplification and one trick pony reduction of multi-purpose computers into toys is where the money is.

When we simplify computers to satisfy simple people

needs, we end up even more oblivious to how they work. When I first started teaching computer technology in high school, I could assume my incoming grade 9s knew how to navigate file management in a computer (that’s deep in the cheese). But as Chromebooks took over I realized that (thanks to cloud based everything), students had lost their understanding of how local files are stored.

RESOURCES IF YOU WANT TO MAKE YOUR OWN PIZZA PC

If you’re curious about customizing your own pizza PC, PC Parts Picker is

a great place to start. Once you realize what’s available in terms of

doughy hardware and what you can do with your cheesy operating systems,

computers suddenly turn from something you barely understand (even

though you use them every day) to a tool that you can fix and customize

to your needs.

Here is the lesson plan we work from when I introduce students to computer architecture.

But the best possible way to get these concepts across to students is to have them build

desktops with their own hands and you can do this FOR FREE! Find the COMPUTERS FOR SCHOOLS program in your province and they will happily provide you with computer hardware to DIY your PC builds. I’ve worked with RCT Ontario for many years and they are fantastic, providing teachers who want to build genuine technology fluency in a hands on way.

Students love building their own machines, but the best part is the EQUITY and INCLUSION it enables. For students who don’t have a computers at home, they can build one and then take it home, making this one of very few times where the education system is actually closing rather than widening the digital divide.

The Digital Divide is Deep & Wide

Using the Pandemic to Close the Digital Divide

How to Pivot Ontario Education to Prepare for The Next Wave

Why Canadian Education is so Reluctant to Move on Digital Literacy

from Blogger https://ift.tt/XF1Kgeb

via IFTTT

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)