Originally published on Dusty World, March, 2014.

The Google Apps for Education (GAFE) ‘Summit’ is this weekend. I’m not there and I’m comfortable with that. There is nothing in Google that I haven’t been able to figure out on my own and I use Google extensively, they make good products.

| Last week’s Elearning Ontario Presentation |

Last week I presented at elearning Ontario on how to create a diverse digital learning ecosystem. You’d think that educators would want to get their hands on as wide a variety of tools as possible in order to not only provide the best possible digital learning support for their students but to also increase their own comfort zone in educational technology. In the mad rush to digitize the vast majority of people want as little expertise to accompany it as possible, they would much rather find a closed ecosystem in which they can develop a false sense of mastery.

If you hyper focus on one thing you tend to get an inflated sense of your abilities. I wouldn’t trust a mechanic who can only work on Ford brakes or a teacher who can only work out of Pearson textbooks, I’d have to assume they’ve learned by rote rather than developed mastery. I know it’s hard work, but becoming fluent in digital tools requires some time, some curiosity and some humility and that’s ok.

If you hyper focus on one thing you tend to get an inflated sense of your abilities. I wouldn’t trust a mechanic who can only work on Ford brakes or a teacher who can only work out of Pearson textbooks, I’d have to assume they’ve learned by rote rather than developed mastery. I know it’s hard work, but becoming fluent in digital tools requires some time, some curiosity and some humility and that’s ok.

|

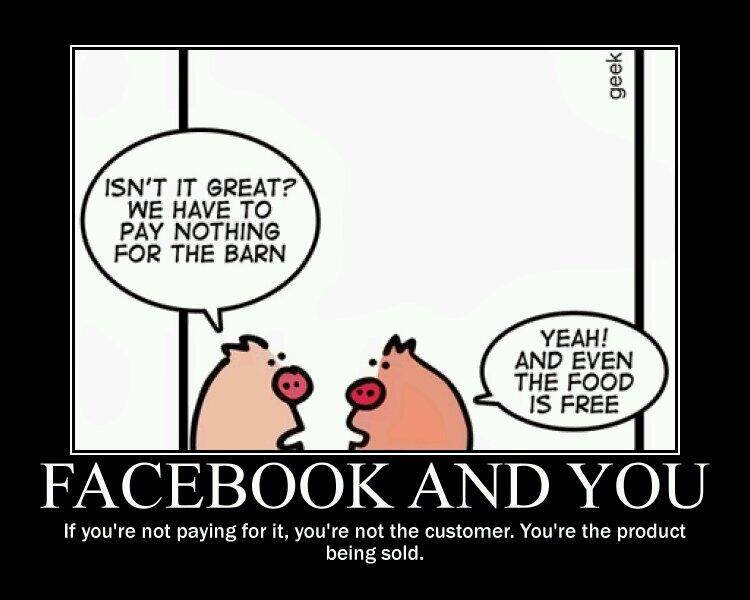

| A colleague showed me this last year and it has been on my mind ever since. |

The idea that you get a qualification under a single brand and have somehow become a master of digital learning is misleading. But the limits of evangelizing a single digital learning ecosystem go well beyond questionable professional practices around branding teachers with private company logos. There is also the question of how these technologies are mining education for profit.

If you live within a monopolistic education technology environment you can never be sure what they are doing with the data they are managing for you ‘for free’. That data is worth a lot of money. Even if it’s being stripped of names, the ethics of exchanging student marketing data for a ‘free’ digital learning environment has to be questioned. In a monopolistic situation that questioning doesn’t happen. Only an open, fair digital learning environment allows us to demand higher standards from companies who are otherwise singularly focused on making money in any way that they can.

| Wouldn’t an opensource hardware model that allows us to teach all technology platforms be a nice idea? The Learnbook |

Some links to consider:

http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/DigitalEducation/2014/04/google_amends_its_terms_on_sca.html

“Google would not answer questions about whether its data-mining practices support the creation of profiles on student users.

Google also confirmed to Education Week that its general terms of service and privacy policy apply to student users of Apps for Education, a stance contrary to the company’s earlier public statements.”

http://www.osapac.org/cms/sites/default/files/Memo%20-%20Contract%20Addendums.pdf

| OSAPAC has worked out a deal that doesn’t sell off Ontario Students’ data, but it’s a secret, and each board has to implement it themselves. The mysteries of information in the information age… |

https://twitter.com/search?q=%23gafesummit&src=typd&mode=users

Tweets on this weekend’s GAFE summit in Kitchener/Waterloo… the koolaid tastes good.

noun

-

1.(in feudal Japan) a wandering samurai who had no lord or master.