I feel great shame. I wrapped up this year’s Ontario Library Association super conference a few weeks ago, but my Kawasaki needed me and I’ve been neck deep in engine heart surgery instead of reflecting on this fantastic conference. Mechanics that my life depends on is sufficiently engrossing.

This was my second go at the OLA Super Conference, I last went in 2023. This year, like the former one, was remarkably emotional. You can’t help feeling that these are the front line people trying to hold civilization together even as it seems determined to tear itself apart. I’m left dizzied by the size of the fight against them.

Tech billionaire oligarchs are leveraging bottomless resources to direct a biblical flood of idiotic panic mongers who are happy to churn out disinformation that buys political victories. Once in power they have the tools to dismantle the critical thinking based education that we all used to aspire to.

Nothing is easier to incite than ignorant, misinformed, angry people. Our tech overlords have designed systems that encourage propaganda and reduce people to shallow, self-contradicting talking heads. I’ve been struggling to get pedagogically meaningful digital literacy into more classrooms throughout my career, but I’m beginning to realize that this is contrary to the direction society is going. Swimming upstream against this big money gets tiring in your mid-fifties.

Libraries standing against this political onslaught are having their resources systemically cut because libraries are precisely the institutions we designed to stop this sort of thing. How do you win such a one sided fight? I’m beginning to think that the democratic elections being gamed by this process can’t produce governments capable of stopping it, and I’m getting all Asimov-Foundations about it. Perhaps it’s time to save what we can for civilization until we start rebuilding again. And yes, these are my thoughts as I watched the Ontario Library Association standing against book bans and funding cuts.

Belief in the mission is one way to keep up the fight, but everyone seems worn thin by the effort. Keeping a strong front becomes difficult when your allies dwindle and everything you’ve built around literacy and critical information analysis is dismissed as meaningless. We live in interesting times. Being able to tie one on at the evening social with the brilliant women leading this fight was a highlight.

Carol Off‘s closing keynote was earth shaking. I wish they’d put it out so more people could hear it. Her retirement from As It Happens on CBC coincided with the rise in hate and division we’ve seen around us. Her talk cut to the quick describing the mechanics of this nastiness in vivid detail. It was a much needed rallying cry even as the barbarians hammer at the gates.

***

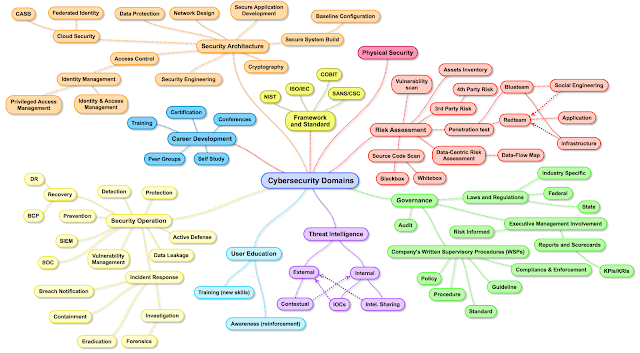

I’d signed up to present at the conference because I wanted to demonstrate (rather than just talk about) the importance of government, civil society and industry working together for our mutual cyber well-being. If you think that’s not a priority, 2025 is only a few weeks old and dozens of Canadian school boards have already been crippled by cyber-attacks, most of which depend on clueless users to get in. The vast majority of our cyber woes are a human education problem, not a technical one.

In the spirit of cooperation I reached out to many cyber organizations, but the common response seems to be a shrug when you’re sitting on a comfortable amount of funding, which isn’t very mission driven of them. I did connect with Debra at Knowledgeflow who is nothing but mission driven and she worked tirelessly to help build our collaboration in a country designed against working together. This ended up being our pitch for the talk:

To demonstrate the width of our collaborative approach, Marie at the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security joined our motley crew along with Cheryl from Cyber Legends. This gave us a full complement of cyber expertise from federal government, civil society and private industry. I can only shake my head at the many other not for profits, industry and provincial organizations who weren’t interested in participating because they’d rather just do their own thing poorly. Gaps caused by these little fiefdoms are why Canada is considered a prime target in global cyber-crime circles.

You might think that school boards are ‘doing’ cyber education locally, but the material I see (if there is any at all) is reductive, outdated, performative and not at all pedagogically valid in terms of teaching skills. Most of the cyber awareness stuff being trotted out locally looks to be made by people with no background or experience in cybersecurity. In many cases the cringy media they produce doesn’t look like it was made by anyone with an instructional background either.

|

| Debra has this slide up in our presentation and suggested that these kinds of systemic failures aren’t something that individuals can influence, but I disagree. If the vast majority (research suggests over 80%) of breaches are caused by someone clicking on something they shouldn’t and letting criminals in past otherwise effective defences, then a skills based approach to cyber-education would also reduce these kinds of headlines! |

Our talk can be found here: https://knowledgeflow.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/OLA-Conference-Cybersecurity-Isnt-a-Scary-Word.pdf and includes piles of material designed by cyber specialists. Whether you’re working with post-secondary, K-12 or even with adults, you will find credible material designed to teach actual cyber skills rather than questionable performative marketing material that checks a box.

A heartwarming moment on day two was seeing Joseph Jeffries and Jennifer Casa-Todd recognizing the yawning digital skills gap in our education systems and tackling digital skills head on with the Canadian School Libraries. Seeing this happen across provincial lines gave me hope as this doesn’t happen a lot in the true north siloed and self-interested.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/VWjin4q

via IFTTT

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)