|

| No, it hasn’t. Prepare to get maytagged by quadmesters for the foreseeable future |

I’m staggering to the end of this absurd quadmester. When it started I wondered if less was all we could manage, and it turns out that it is. From administration dismissing concerns about masks that don’t fit (or really matter when you can catch COVID through your eyes) and are so far beyond of Health Canada and local health unit expectations that they end up being more restrictive than needed and not at all designed for all-day use (especially while performing instruction), to a schedule that seems explicitly designed to download an abusive amount of work on classroom teachers with the highest class caps, this quadmester has been a disaster.

The lack of focus on what we’re supposed to be doing (providing effective and differentiated instruction that maximizes student learning, remember?) suggests that these things never really mattered in the first place. Got special learning needs? Too bad, special education support is cancelled. Find keeping up with school difficult? Too bad, we’re going to fire you through courses at record pace even though everyone is reeling from a pandemic. Don’t worry though, it doesn’t really matter if you keep up or not because you’re getting credits regardless.

I’m able to provide interactive, relevant online learning opportunities for my students and even I still struggled with between 20-40% disengagement in remote learning this quadmester. I’ve heard of other classes that just did nothing online. If you talk to admin about it they’d rather pretend it’s happening than do anything to ensure it is with anything like quality in mind. I had a class drop down to twenty students which means it could have become a single cohort and I could be their online instructor, but making a change for pedagogical effectiveness that would have alleviated a staff member’s medically supported issues with the provided face masks wasn’t something anyone had any time for.

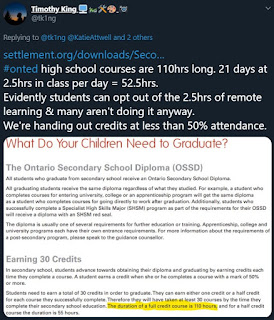

I recently learned that students can opt out of remote learning entirely if they want. This has resulted in kids who have attended less than fifty hours of instruction earning Ontario high school credits this quadmester (Ontario high school courses are supposed to be 110 hours of instruction). Remote learning with a teacher unqualified or even knowledgeable about the subject (as was my case with both of my online support teachers) can’t be called instructional time anyway. ‘Quadmester’ should be changed to ‘freemester’ or ‘fakemester’.

As I wrap things up from my double cohort/teaching continuously all day/double class/teaching continuously every week quadmester one I’m struck with how this drink-from-the-firehose schedule that doesn’t remotely meet Ontario standards not only injures already traumatized students and staff but also removes the most challenging work I do in class.

We got to the culminating projects (exams are cancelled – as is all safety paperwork because why not) and I found that my grade 9s have not had the opportunity to develop a rigorous and resilient engineering process in the way that they would in any other year, though considering the class is half as long as it should be I shouldn’t be surprised. I’ve been able to cover the basic material, though the speed at which that came at students was overwhelming even to the stronger ones. Neurologically speaking, you need time to reflect and internalize new learning, but best pedagogical practices have long since been flushed down the toilet.

I keep hoping that we’ll make adjustments toward making Ontario education more equitable and fair to everyone as this slow burn pandemic grinds on, but the powers that be appear to believe that they are finished and are ready to fire us through quadmester after quadmester rather than responding in a best practices-continuous evolution. I’ve suggested previously that the week-on week-off is already problematic, so why not just go back to week on week off semesters? If we did that with a Friday fully remote review day we could also give teachers and students the headspace they need to consume new learning, but the new normal is too waterboard everyone with a pedagogically bankrupt schedule that only has the appearance of credibility.

As we lurch into quadmester two with no quadmester ending in sight I’m looking forward to not being waterboarded any more, but I’ve still been handed another technology course with two cohorts and a teacher who has no background in my speciality ‘covering’ the remote part of the course, so I can expect another poorly engineered schedule designed to hand out cheap credits. I got handed the same thing (a course I’m not qualified to teach) to provide remote support in even while I’m still providing technical support to people across the school and beyond. There is evidently no way to differentiate teacher schedules to give them time to provide system support either.

I’ll do what I can to mitigate this poor scheduling (again), but since the system has downloaded all guidance and special education expectations on me as well I’ll be stretched (once again) to the breaking point trying to protect students from a schedule designed by people who don’t seem to care for their personal circumstances and well being… while struggling through a pandemic with my own health concerns.

Even evidence that the system think types are evolving this in the right direction would be helpful, but communications are nearly non-existent and there is no sense of vision or even an acknowledgement that what we’re doing isn’t kind, let alone working. The new normal is a cruel, undifferentiated and ultimately meaningless place. With a complete lack of leadership from the Ministry or Minister, we’re likely to see Ontario plunge in years of darkness as a result of this overwhelming and cruel schedule.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2IkbTRF

via IFTTT