|

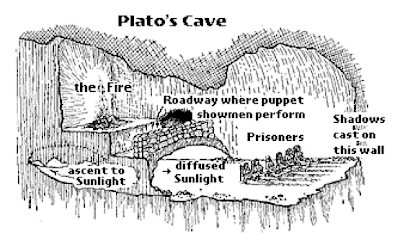

| The digital house of mirrors we all live in. |

It’s early days, ECOO isn’t until next October, and I’m reticent to say what I’m going to present on months ahead of time. The digital learning landscape can change quite significantly in eight months.

My previous ECOO presentations have followed an interesting arc, from philosophy to specific action. My first go with Dancing in the Datasphere talked about fundamental changes happening to us as we transition to a data driven world. The mini-lab followed a year later, the idea there being that we diversify technology in order to develop true digital fluency in students. Last year the final step was to work toward a digital skills continuum. Only by integrating a developing skill set into curriculum will we begin producing students who have the technical skills necessary to survive and thrive in the digital age.

That trajectory, no doubt pushed by my transition to computer studies from English, had me looking at developing greater student familiarity with computing tools because I see a great deal of ignorance in the ‘digital natives‘ I’m teaching every day, but that focus was technically biased.

For those of us who have lived as adults through the last twenty years of technological revolution, we sometimes forget where we’ve come from because we’re so engrossed with where we are. For ECOO this time round I’m thinking about what technology is demanding of us as people. Our selves are being stretched and amplified in ways they never have before. Nick Carr’s The Shallows puts us on a pretty stark trajectory towards idiocy with what is happening to us. The digitization of the self stretches us flat, making continuity of thought impossible and turning us all into distracted, simplistic cogs in a consumerist machine designed to turn us all into the lowest common denominator; none of us any smarter than our smartphones.

With the advent of social media we suddenly find ourselves existing in multiple places at once. Our self is no longer geographically focused. Our influence spreads across the internet. We are able to affect change in people and places formerly unconnected to us. The people we communicate with (albeit in a minimalist way) are far flung and many. The people we spend deep, attentive time with are fewer and diminished.

Our digital selves are perceived in many different ways. The aforementioned digital native tends to not differentiate between online and real world action. They often consider social media as just another conversation they are having, and are then shocked when something said publicly is responded to by the public. The generation of kids (our students) growing up in this ongoing social experiment never look at privacy settings, have little idea of the differences between social networks and tend to broadcast online what is on their minds in much the same way they would while hanging out with friends. The veil between the physical and the digital, between public and private is all but non existent to them.

| Digital Footprints & Always On Teacher Faces |

A more professional approach to managing the online self is to adopt marketing theory and develop your online brand. Companies and celebrities approach social media in this manner, often using marketing firms to manage and run their social media presence. I can’t help but think that this lack of genuine presence games the system and ultimately fails. It’s exhausting to maintain if you can’t hire marketing monkeys to run it for you, and ultimately, it’s fake. I’d much rather read my favourite author’s tweets from his own fingers than follow what someone trying to sell me something thinks I should be seeing. Many teachers fall into this trap when tentatively stepping into online presences. Spending your weeknights and weekends being mister or missus Teacher is nothing more than working all the time, forever.

|

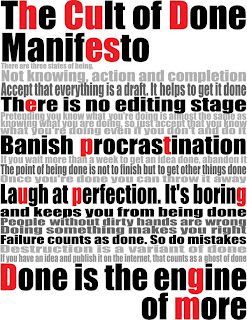

| The Cult of Done |

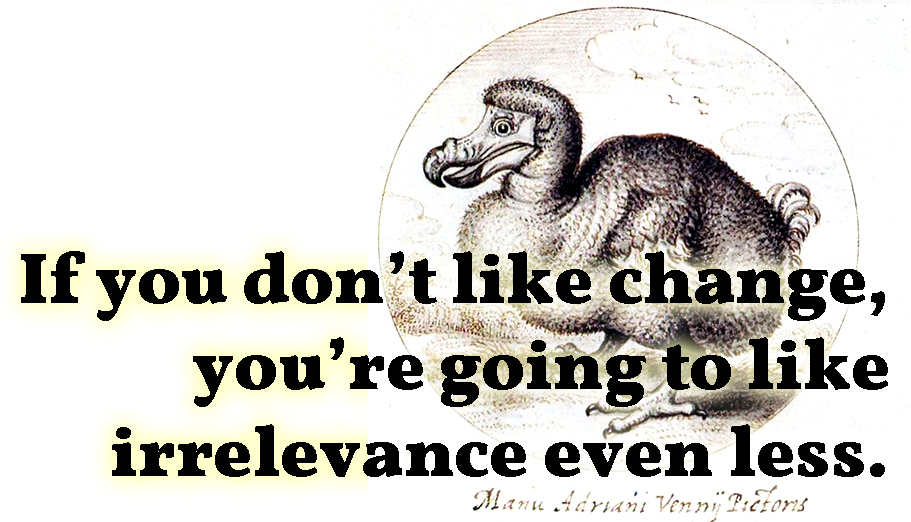

If there is a positive future to a digitally enhanced self I’d hope it is through a genuine sense of self expression. We should be aware of what the tools are and how they work, and then we should use them to empower our access to information, our ability to mine deeply into details, to collaborate and develop community, to share our own creativity, interests and sense of discovery. The technology should not only allow us to do these things, it should be pushing us to maximize our effectiveness as thinkers and doers. Any technology that produces distracted idiots will doom the people using it. Evolution should still be eliminating the irrelevant, even in the digital realm.

It’s early days in this sea change of how we deal with a digitally enhanced self. In the future the hybrid intelligence of a digitized human will evolve toward a higher order of effectiveness. Those made useless by digital tools will, much like those weakened by an inability to read, become marginalized. Those able to harness information literacy will enjoy those advantages. Those who ignore it will find themselves increasingly unable to compete.

What that effective digital self looks like in students, in teachers, in people in general is where I’m currently thinking about pushing my research this year. How we adapt to these changes now will establish effective habits as the technology rapidly spins out of its infancy and into maturity. There is no better time to consider what a digitally enhanced human being should look like than now, when we’re in the process of inventing the very idea.

The idea of Web3.0, or intelligent/self organizing information suggests that the future of digitized humanity will inherently push toward greater effectiveness. The opportunity to be passive or stupid in a digital context will actually work against what the data wants to do for you; you’ll learn in spite of yourself, you’ll know what you need to know when you need to know it – the data itself will ensure this. It would be interesting to show the evolution of digital humanity over the past three decades, and where it might be going in the next twenty years.

The era of stupid/passive information is ending. The people that it has created will have to adapt to technology that demands more of them, or risk being made irrelevant by it.