| Tweets from the #edinnovation Summit |

Listening to the urgency and paranoia in these discussions had me thinking about how privacy and data ownership are framed in digital environments. I’m the first to suggest we be cautious with how student data is shared, but the idea that anything digital can somehow be locked down and owned is ridiculous. I’ve heard ed-tech ‘experts’ go on about walled gardens at length. You can leap over any of those walled gardens with a simple screen capture or text grab, and then it can go viral on the wild internet. Trying to keep data in check is like trying to hold back Niagara Falls with a door, digital data is incredibly fluid, that’s why we can do so much with it.

Listening to the urgency and paranoia in these discussions had me thinking about how privacy and data ownership are framed in digital environments. I’m the first to suggest we be cautious with how student data is shared, but the idea that anything digital can somehow be locked down and owned is ridiculous. I’ve heard ed-tech ‘experts’ go on about walled gardens at length. You can leap over any of those walled gardens with a simple screen capture or text grab, and then it can go viral on the wild internet. Trying to keep data in check is like trying to hold back Niagara Falls with a door, digital data is incredibly fluid, that’s why we can do so much with it.

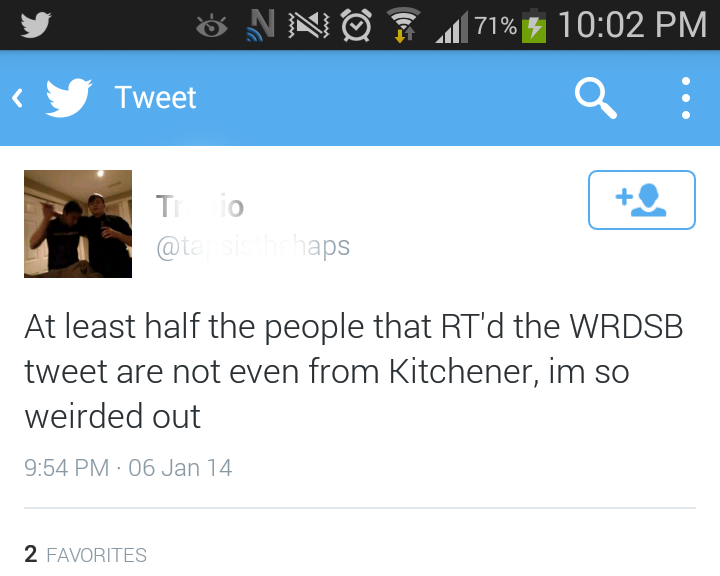

The second tweet at the top sheds some light on how we are misframing data as an ownable entity. Like your appearance or your reputation, the data you give off is information you emit socially; you can’t own your data any more than you can own your appearance or your reputation. In all three cases you can, of course, influence the social outputs you’re giving, but you can’t own them. Realizing this would stop us from trying to control the uncontrollable and instead let us begin teaching students (and everyone else for that matter) best practices for creating desirable data emissions (there has to be a better word for that, digital reputation? digirep? virtual scent? vBO?).

If we begin to see digital data emissions as a natural byproduct of online interaction (and make no mistake, they are), then the idea that if we throw enough money at it we can make everyone safe gets questioned. You’re never going to hear education technology companies that market based on security suggesting this mindset, there’s no money in it.

The other side of this is privacy. The idea that we can suddenly have privacy now when we’ve never had it before is baffling to me. Before we became industrialized we were mostly geographically locked to where we were born. Without the ease of fossil fuel powered vehicles most of us never travelled more than a dozen miles from where we were born. Do you think anyone had privacy in those circumstances? You were a well established element in a fairly static society. The idea that you could shield your actions from the public eye only really began in the twentieth century. Industrialized anonymity was as much curse as it was something desirable. It was only in the conformity forced on us by industrialization that the illusion of privacy existed.

|

| If the NSA and CIA can’t stop it, do you think that edtech companies can? |

We are emerging from that drab, industrial anonymity caused by cookie cutter conformity. The digital world doesn’t expect us to be passive eyeballs counted as ratings in front of a TV screen, it demands interaction and individuality and it restores our voices. As we emerge into an individually empowered, digitally driven world of shared information, expecting privacy is a wish for a poisonous illusion that never really existed.

Privacy isn’t dead, it never existed. Prior to industrialization we had no social privacy at all and during industrialization we were dehumanized into bricks in the wall and given the illusion of privacy because we barely mattered as individuals.

When you’re online nothing you do is private, nothing you do is owned by you. Just as you can influence your appearance by good hygiene or your reputation by performing right action, you can affect your data-appearance by presenting yourself well, but ultimately any data you give off is out there and can spread easily, just like gossip.

The nascent study of digital citizenship addresses a lot of this, but like other digital skills it is an afterthought, never integrated into core curriculum. No wonder men in expensive suits can make lots of money preaching fear and convincing educators to spend their budgets on myth and innuendo. Perhaps one day educators will take the job of understanding and teaching digital skills seriously and ignore the snake oil.