The primary function of Dusty World is for me to reflect on my teaching practice in order to resolve problems. This one’s going to sound like a lot of complaining, but it leads directly to the following posts that suggests outlets and ways to manage this overwhelming curriculum.

***

I’ve long had difficulty managing the byzantine history and fractured approach to computer technology in Ontario high school classrooms. Our subject council email is clogged with desperate pleas for qualified teachers to fill absences that, if not filled, will result in the closure of programs; most of them don’t get filled. Meanwhile, existing computer-tech programs are treated as an afterthought, often overloading teachers and students with multi-stacked classrooms.

A colleague recently noted that less than 30% of Ontario high schools even offer the computer technology course of study. In 2018, being able to make effective use of computers is a fundamental skill that will assist students across the entire spectrum of employment and post-secondary training, yet few students enjoy access to this vital Twenty-First Century skillset. If you can get a computer to work for you, you immediately have a socio-economic advantage; fluency in computer technology is foundational skill in the Twenty-First Century, but only 30% of students in Ontario can access it?

Ontario technology curriculum is based around absolute skills arranged in a hierarchy, so as courses progress they become less and less accessible to students with no previous experience. This is at odds with the TEJ3M curriculum that describes the course as having no pre-requisite, yet the technical expectations of TEJ3M are complex and wide ranging (starting on page 76 – give them a read, they’re astonishing). In post-secondary programs and industry, any one of the strands in this curriculum would be its own course of study and most are degree programs, but in Ontario high schools they are all lumped together in a course with no previous experience required.

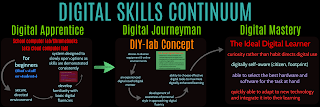

Ontario technology curriculum is based around absolute skills arranged in a hierarchy, so as courses progress they become less and less accessible to students with no previous experience. This is at odds with the TEJ3M curriculum that describes the course as having no pre-requisite, yet the technical expectations of TEJ3M are complex and wide ranging (starting on page 76 – give them a read, they’re astonishing). In post-secondary programs and industry, any one of the strands in this curriculum would be its own course of study and most are degree programs, but in Ontario high schools they are all lumped together in a course with no previous experience required.Many students, even those who have taken the optional junior TEJ course, struggle to grasp the wide range of knowledge and build the experience required to cover the 3M curriculum. Senior TEJ M-level courses are the equivalent of asking a student to walk into senior advanced science with no previous experience and then study biology, chemistry, environmental science, space science and physics simultaneously. All of this highlights Ontario education’s poor handling of computer technology. Yet fluency with information and communication technology is becoming a fundamental requirement in pretty much every pathway a student can choose in 2018, while specialists in the field enjoy clear advantages in the workplace. I feel I’m well within my professional scope to revise and make these poorly formulated requirements more accessible for my students. In the process I hope to address, in a small way, the digital illiteracy that plagues Canada’s (and the world’s) population while also supporting my digitally focused experts.

The fractured computer technology curriculum is one of many reasons why there are a dearth of educators qualified to teach computer tech (less than 30% of Ontario high schools even offer the subject). Our subject group frequently gets emails saying programs from ICT to robotics will be shut down unless a qualified teacher can be found, but there are none available. This seems at odds with how many computer tech programs are treated in the few places they exist. In our own board we have schools closing down irreplaceable computer tech labs in order to support subjects more designed to entertain than employ.

The few teachers willing and able to take on digital technologies are overwhelmed by the expansive curriculum they are expected to attempt. My technical background was as a millwright and then a computer technician. I am professionally competent in information technology and networking and have a considerable (though not equal) amount of experience in electrical work. My experience in electronics is passing at best, but I make do. My coding background, which I’m also supposed to be an expert in, is mostly self-taught (Ontario has been failing to provide an applied technical education for computer focused students for decades). Finding a teacher who can teach the Ontario computer technology curriculum is the equivalent of finding someone who isn’t just qualified academically in multiple fields, but is also has working experience across multiple industries; if they do exist they are polymaths making millions. We accept science teachers who have never worked a day in the private sector, but computer technology teachers are required to show years of industry experience in addition to academic qualifications.

Then there is cost of teaching tech. I used to take home about $920 a week as a millwright in 1991, and that was with a full pension and benefits package. As a senior teacher with 13 years of experience, 5 years of expensive university training and three additional qualifications including an honour’s specialist I had to spend months and thousands of dollars on, I bring home about $250 more a week in 2018. I often wonder why I’m teaching when I could have been making a lot more doing what I’m teaching, and with a lot less political nonsense.

| The vast majority of Ontario Education is designed to feed that 10% unemployment rate in the Canadian youth job market. |

Then there is the split focus of Ontario education with digital technologies falling somewhere in between. If you teach in academic classrooms you’re what the whole system is designed around. If you’re teaching a hard tech like transportation, carpentry or metal shop at least you fall into another category, albeit one that is often treated like more like a necessary evil than a valid pathway for millions of people. However, digital technologies get the worst of both worlds. Hard techs have reasonable course caps of 21 students in order to ensure safety. Academic courses in standard classrooms get capped at 31, but digital techs have no specific Ministry size limits and are capped at whatever local admin wants. At my school that’s a class cap of 31 students, the same as a senior academic English class, which is absurd. 31 students might work (barely) when you’re working out of texts in rows, but trying to teach 31 students soldering with guns running over 400 degrees, or working inside computers with power supplies powerful enough to knock someone unconscious?

Safety is a constant stress in the computer tech lab. We’re expected to maintain all the same safety standards and testing as hard techs, but with a third more students. On top of that, since my classes are capped at 31, if 20 students sign up for it (which would run as a section in any hard tech), my courses are dropped or combined into stacked nightmares of assessment, management and differentiation. Classes that only load to 60% are usually cut. Last semester I had five preps, four of them in one period. If you think the breadth of computer technology curriculum is already too much, try teaching it in a stacked class with four (4!) different sections at once. The majority of computer tech teachers experience this joy every semester. Taking all of this into account, it’s no wonder there aren’t more computer technology courses running in the province.

With little hope of the curriculum getting sorted or computer technology being treated as anything more than an afterthought, I’m still working to try and make my courses as applied, effective and accessible to as many students as I can, because it’s important that young people understand the technology that so influences their lives. If more people knew how it all worked, we’d have less abuse of it.

I spent time on March Break getting my heart tested because I’ve been having trouble sleeping and have been getting a jittery feeling in my chest. My doctor tells me I’m strong and healthy physically, the nerves and jittery feeling are a result of stress. I can’t imagine where that comes from. He suggests I take steps to reduce it, but I told him it’s not in me to mail in what I’m doing. I find teaching to be a challenging and rewarding profession and I believe my technical background is an important field of study. I tend to dig my heels in when I believe that something is important, even more so when there is systemic prejudice against it. I intend to keep fighting for what I believe is important learning for my students, but this is one of those times when swimming against the tide of indifference feels overwhelming.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2Gs6xlm

via IFTTT