Part 1: What do you take with you into the future?

We live in a time of radical transformative social change. One generation’s experience is markedly different from the next. How we communicate with each other dictates our social structures, and we are in the middle of a communications revolution. In times like this many traditions and habits fall by the wayside. If you have to cling to an ideal in order to ensure it survives this sort of disruptive evolution, what ideal do you cling to? After hearing a colleague describe themselves as unionist, and experiencing my own fall from grace, union isn’t what I choose to protect at all costs. In fact, like many other institutions founded at the dawn of industry, unions and local boards are beginning to appear less and less able to deal effectively with our times.

I didn’t become a teacher to support unions, I became a teacher to support educational excellence and hone my profession. Protecting education means protecting educational workers, but protecting educational workers does not necessarily mean protecting education. I was initially hesitant to become active in my union because of their blanket coverage of all members, regardless of competence. The occupy movement and the radicalization of economics in the past few years pushed me into action; at least unions offered protection from this short sighted narcissism. So many people are happy to give away their rights in order to dream of being rich while being made serfs. My union offered me a political mechanism to fight that idiocy.

I don’t join things easily, I tend to skepticism, but OSSTF claimed moral high ground on so many issues that I couldn’t help but become a believer. What’s not to like about an organization that claims democracy and is founded on the idea that wealth should be fairly divided and members should consider the common good before their own?

When times were good accounts were managed well. Grievances were dealt with, expectations of the membership were minimal, people focused on the important work at hand. In the past year we’ve come face to face with a government that appears to have no moral centre whatsoever, and a public that is more than willing to be lied to in order to become incensed with us. The resultant mess has me asking some hard questions about the antiquated organizations involved in our education system.

There is a lot of history tangled up in how we manage education in Ontario, and I don’t think it’s creating a transparent, representative system. We’ve got local boards that don’t actual bargain with their employees anymore, we’ve got local unions that don’t actually bargain for their members anymore, we’ve got a College of Teachers who got chucked into the mix the last time a psychotic government decided to play fast and loose with education, we’ve got a Minister of Education who has more in common with Mussolini than John A. MacDonald, and carnage across the province with strike days, almost strike days, crippled extracurriculars and frustrated citizens on all sides. If you think this has been well managed by any of the combatants involved, you must be crazy. I argue that this is the result of a tangled, historical organizational mess, and it’s time to move Ontario’s education system out of a Victorian mindset.

In what follows I’m considering alternatives that actually protect education workers (what we have now obviously does not), and puts the focus on our profession rather than the antiquated political structures around it.

Part 2: Behind The Times

The stumbling approach to this last round of bargaining suggests that unions are having real trouble dealing with twenty first century realities. From social media causing a surprise grassroots movement that bypassed provincial executive plans to a stubborn refusal to change their ancient communications habits, unions in general and mine in particular have looked like confused Victorian gentlemen at a rave.

Local boards, like union locals are in even more trouble. They have been made redundant, looking on as the provincial ministry directly bargains with provincial union organizations. There is no local bargaining in Ontario any more. With so many vestigial political interests around the table it’s no wonder that Ontario’s education bargaining has been a mess this year. Perhaps it’s time for a historical cleanup.

I’m now wondering what Ontario education would look like without local political interests like boards and unions, assuming that we can find other ways to protect this vital resource in a centrally bargained environment. The old players certainly aren’t protecting quality of education, in this past round of bargaining they haven’t done anything at all except watch as provincial heavy weights speak over their heads.

This questioning began when @banana29 shared this article that questions the value of unions in Ontario education. If you can get past Wente’s heavy handed right wing propaganda in the first few paragraphs, the piece asks some hard questions about the role of unions in maintaining status quo in an education system that struggles to keep up with our times. Her intent is to dismantle public education and infect it with market interests (it is the Globe & Mail), my intentions are quite different.

Part 3: Wente Article Response:

Technology In Education and institutional drag

Wente makes some pretty simplistic arguments for technology in education. If you think Khan Academy is the future of education then you’re about as pedagogically sophisticated as a donkey. Having said that, technological implementation in education has been slowed at every turn by boards and unions, both of whom have frantically told teachers not to use new communications mediums to communicate with and teach students. Running at the speed of the slowest adopters of technology is no way to run a relevant education system.

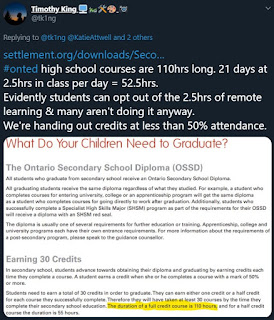

Technology being used in classrooms lags years behind what students experience everywhere else, and doesn’t begin to prepare students for the rapidly changing world they are graduating into. Teachers struggle to engage students on antiquated software and hardware, and no one wants to consider what a teaching job beyond concrete walls looks like. It behooves the unions and boards to keep school in the classroom where the have a lock on how to manage education as a production line. Ask any teacher who has done elearning how their non-standard work hours become a real problem to both boards and unions.

Not only does this luddite thinking infect the classroom, but also the management of both unions and boards. Communication with members remains firmly stuck in the last century. Video meetings? Shared online resources? Social media? These things are adopted hesitantly or actively discouraged by parochial thinking. Teachers using them then bypass local roadblocks because that is what modern communications are capable of. From unions trying to control a message to boards trying to limit student access to communications – information is flowing around these road blocks on smartphones and social media, yet they don’t realize how irrelevant their control mechanisms have become.

Instead of encouraging teachers to experiment with new technology, local interests tend to parrot panicky, unfounded broadcast media ideas about them. We are ruled by ignorance and paranoia when it comes to technology in education. The question is, how do we create an education system that can experiment and advance at a reasonable rate without being slowed by the insular thinking of its slowest adopters?

Can you protect education without a union?

In spite of its shortcomings Wente’s article did make me wonder, what would education look like in a future without a union/board system? I speculate on this not as a means to dismantle, demean or weaken the profession. I am under no illusions, teaching needs to be protected from short sighted business-think, but after watching McGuinty’s Liberals gut years of collective bargaining I wonder if unions are the right social mechanism to protect us anymore. Could education prosper and even improve without union/board paradigms?

Centralizing control is happening already. Modern communications will continue to force this change whether unions or boards like it or not. If we’re going to evolve from a parochial, historically restrained system to something adaptive and forward thinking, we need to think of a new way to organize and manage the vital social service that is education in Ontario.

Part 4: Education: an essential service

Vital is exactly what education is. A first rate education system means that all the other essential services (police, medical, fire) have less to do because the populace isn’t feral and desperate. A properly run education system means the vast majority of the population comes closer to expressing their potential. It means that socioeconomic status isn’t the prime breeder of crime and poor health; failure is less an excuse of circumstance. Good education means less people in jails, greater economic output and interested, active citizens powering our democracy. In this context, how could anyone not see education as an essential service?

Education should be declared an essential service. This automatically guarantees third party arbitrated contracts, which would mean that bargaining isn’t the wild west that it is now, and governments couldn’t simply bypass it with cynical, undemocratic laws like Bill 115. It would also mean that militant unions aren’t necessary because the system in place would be implicitly fairly bargained.

Arbitrated bargaining would also take the unionized target off teachers’ backs and let them adopt a more professional aspect in the public eye. Education workers would still be protected, but the system itself would be the protection. Depending on militant unions hard bargaining with local boards didn’t work and has evolved into unrepresentative (OECTA) or misrepresentative (OSSTF) provincial bargaining. Our process of bargaining is a broken, divisive, old fashioned habit that antagonizes the general public, vilifies our profession and makes hay for cynical governments.

Part 5: Freeing ourselves from history

local vs. provincial bargaining

When union locals used to bargain individually with their school boards each area’s special interests were baked into contracts. This made sense because of Ontario’s vast size and the unique and isolated nature of its many settlements. If you travel around Ontario now you’ll see the same Justin Bieber haircut everywhere. Clinging to isolationist thinking in an information revolution is asinine. Communities are no longer isolated, they no longer need individual contracts. If you don’t believe me, believe union provincial executives who (foolishly I think) agreed to align all contracts in the province resulting in this past round of failed provincial negotiations.

|

| The fictional professional association for education professionals in Ontario (except it shouldn’t be fictional and we shouldn’t be running education on socialist ideals, it’s a profession!) |

If we can bargain provincially (and it appears we do), why not have an Ontario Educational Association (modeled on the Doctor’s OMA) bring in elected representatives from across the province every four years to iron out a contract with the government while a neutral, third party arbitrator ensures the process is fair. This is a far less dramatic, adversarial process, but I think everyone in education (except the ones who profit from the fighting) would like to see less hurtful public drama and more focus on the profession itself.

Unions themselves have made their locals irrelevant by focusing their own membership through isolated, politicized provincial leadership. The result has been confusion and a failure to represent member’s interests. OECTA agrees to contracts without even asking its members, OSSTF has the rug pulled out from under it by a grassroots social media movement. Unions have centralized power and are then astonished when their remote members aren’t thrilled.

It’s time to give up the idea of locally defined educational organizations, both boards and unions, and begin a process of creating a democratic, less politically tangled system of educational representation. This isn’t so much a matter of amalgamating existing districts as it is a rethinking of how best to represent educational interests in the province. A system based on current cultural divisions (rural-natural, rural-agricultural, small town, suburban, urban) would certainly allow us to continue to address regional differences without carrying the weight of a redundant, regionally defined historical system.

how many public school systems do we need?

If we’re trying to free ourselves from history, it wouldn’t hurt to stop funding semi-private, religious schools that are only willing to serve a specific population.

Once again, this made sense in Ontario a long time ago when Catholics and Protestants had to agree to live together, but Muslim, Hindu, atheist and every other stripe of religious belief must all wonder what this is all about when they first arrive in Ontario. These people constitute the vast majority of new Ontarians, it’s time to recognize that in a representative, equal for all public education system.

Part 6: Removing politically inflicted value in our education system

I’ve always had trouble with how unions favor (and reward) seniority over any other contribution to the profession; at best this is simplistic, at worst it encourages disengaged senior teachers to interact less as their careers mature (check out who is doing extra-curriculars in any school for confirmation of this). We are one of the few professions that, as one colleague once put it, “have all the colonel level people sitting out of leadership positions, we’re led by lieutenants.” This is entirely the result of union value theory, and it harms the profession.

The basic job of teaching, if grossly simplified, becomes a person doing minimal hours of work, with nothing value added, using the same lessons year in and year out. Ultimately this hurts the learning environment for everyone. Unions and boards protect the (small minority) of teachers who approach the profession in this appalling manner more than they do teachers who push boundaries and attempt positive change. Status quo thinking defines most educational leadership.

We need to recognize all the ways that education workers add to the learning process. This usually falls short when management attempts to grossly simplify the work in order to quantify it. If we’re in the job of marking students in creative, individualized ways, we have to do that for educators too, but too often teacher assessment is simplistic or made meaningless in order to simplify book keeping or to protect union members at all costs.

Leadership positions in teaching also need to be made meaningfully. Forty bucks a week doesn’t cut it (yes, that’s what many department heads get for management work in teaching). I’d also want to recognize teachers who do extracurriculars, if not financially, then at least through minimizing their required duties. The teachers who do little else could do oncalls and caf duties, those that are knocking themselves out to make their schools a learning community shouldn’t be ignored for it.

The desired result in all this would be competition for headships and extracurriculars (and administration positions) with top candidates selected. You seldom see more than a single sacrificial person dropped into any of these jobs – not exactly the way to get the best candidates. Lineups for leadership, coaching and non-classroom school activities would be a powerful way to move us forward. It’s sad year in year out hearing the teachers trying to run these things begging for people.

There is a climate of apathetic mediocrity in our unionized system. Members tend to be indifferent to their union and uniformed as to their work situations. They are encouraged to do as much or as little as they please, knowing that the money will always increase; hardly an environment that fosters engagement and improvement. If we want to continue to focus on improvements in education, we should be considering what is needed to put education first, not what is needed to keep the status quo.

Conclusion

Protecting education means protecting education workers, but protecting education workers does not necessarily mean protecting education. It is vital that Ontario’s public school system continue to improve its high standards and fight for relevancy in a rapidly changing world, but the old paradigm of this happening only on the back of unions and boards is dying; their failure is indicated by their inability to protect and support their members.

A mandated, transparent, less politically charged, non-localized organizational structure would result in less drama and better representation for everyone involved. Advances in communication mean that we no longer need to think locally in geographic terms. It would also remove the stigma of unionization from teachers and allow them to adopt a more professional aspect in the public eye.

Walmarting the profession to U.S. standards will result in U.S. standards. You’ll end up with business wanting to intervene with Charter schools, which aren’t really public at all. Equality of access to education is vital to any democracy, Ontario citizens must not lose access to a fair, open, world class public education system. Never suspect that a system with a for-profit middle-man will outperform a public system founded on excellence. You’d have to be an economic idiot (or con artist) to suggest that this is possible.

It’s vital that public education be protected from the short-term gain crowd. Unions have performed this function for many years, but in recent times, and like so many other institutions founded before our age of communication, they are being bypassed by their own member’s new-found ability to communicate directly with each other.

We keep slipping into an inevitable future, and we’re often only able to bring what we hold most dear to us across the threshold. Many assumptions and traditions are slipping by the wayside as society and technology continue dancing at an increasing tempo. If I have to cling to a belief and have it survive this transformative time, it isn’t unionism, localized education or even a political belief, it’s an axiomatic declaration about the power of public education:

Equally accessible, professionally driven and maximized public education is vital to our future success. It allows everyone to realize their potential regardless of their socio-economic circumstances and creates a population that is capable of responsible democracy, meaningful economic output and reasoned problem solving; without it we are lost. The society that protects and enhances public education is the society that produces active citizens whose eyes are wide open, and who are capable of dealing with the challenges technological, social and personal, that we will all be facing in the difficult decades ahead.

I would protect that belief before I worried about keeping the politics of tradition. I would have my profession managed and led on the basis of excellence and engagement rather than nineteenth century, socialist, union ideals. By protecting and encouraging excellence, we could rejuvenate Ontario’s tattered education system under a reasoned, unpoliticized, professional ideal.