In response to: https://www.tvo.org/article/no-more-extensions-its-time-to-cancel-the-school-year

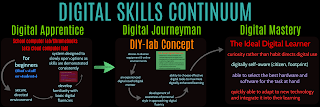

Nam Kiwanuka’s opinion piece on on TVO about why it’s time to cancel the school year highlights many of the problems with technology integration in Ontario’s education system. As a computer engineering teacher in the system I’ve been continually frustrated by Ontario’s lack of focus on developing digital transliteracy in our education system. There are no clear expectations around staff using digital tools and little to no PD around developing fluency in them. Student digital transliteracy is at best sporadic and usually based in if they happen to luck out and get one of the minority of teachers who have personally decided to make themselves literate in 21st Century communications mediums.

Here are some of my reflexive responses to Nam’s article:

“When the government announced its plans for e-learning, I was excited.”

I was not excited, I was frustrated that weeks had gone by with no direction. I was frustrated that at a Ministry level we evidently had no emergency planning in place at all since it looked like it was being made up on the spot. I was frustrated that at a board level we had no idea what digital infrastructure our staff or students had at home. That mismanagement aside, I was worried about what was about to happen. I’ve taught elearning for over a decade and I’m well aware of the challenges involved in it. It came as no surprise that this mandatory elearning government was going to move aggressively in that direction and I knew how unprepared the vast majority of staff and students were to make the move.

“the technology that is being used is problematic. Some of the links the teacher sends work only on certain platforms. So if you’re using a Mac, surprise (!) — you need a PC to access the video. Teachers also send scanned documents that need to be printed, filled in, and then uploaded to Google classroom. So you don’t just need computers and Wi-Fi: you need printers, too.”

There was little or no direction on how teachers should be rolling out remote learning. Other than teachers themselves successfully re-framing this as emergency remote learning instead of elearning (because this is much more than just elearning), we were left in the dark. With the vaguest of directions in terms of hours of work expected (which brutally ignores how students with special needs are supposed to address the work load) and many staff without the necessary tools let alone the skills needed to use them, the best that can be said about emergency remote learning is that it has cast a bright light on our digitally illiterate system.

There are digitally transliterate teachers and organizations who have for years advocated for a coherent development of these skills. The platform dependent work Nam describes above is a great example of digital illiteracy, though I have to admire the teachers in question for trying. It’s like watching someone who can’t read and write scrawl out chicken scratch on a page that no one else can make sense of.

Gary Stager’s principles for teaching online recognizes the limitations of the medium (and the situation) and offers clear and simple steps to making online learning work, but nothing like this was shared with teachers in Ontario. The two weeks of silence following March Break were followed by an announcement that teachers will take it from here. What we were taking and where we were taking it never came up.

“What kids are missing during this pandemic is not homework. What they’re missing are daily interactions with their teachers and their friends.”

The frustration here is that we are actually at a point where our technology could have done this for us, but we’re not literate enough to use it effectively. There are a number of reasons why we can’t leverage technology in education to meet this need.

Firstly there is the digital divide in socio-economic terms. If you fire up your video sharing and get 17 of your 28 students on there I suspect most remote learning teachers at the moment would be giddy with that participation rate, but that’s only about 60% of your students. A number of them won’t have a device that can do it, the bandwidth to see it or the technical skill needed to put all those pieces together, which itself is predicated on access to technology they can’t afford or haven’t prioritized at home.

Let’s say we level the playing field in terms of access. School boards across the province have done back-flips (with no direction or support from the Ministry as near as I can tell) trying to get tech out into student’s hands. A number of years ago I worked with our student success teacher getting refurbished computers out to families in need, but it was a disaster. If you hand people who can’t read a pile of books it doesn’t help them read any faster. All that effort is yet another cart before the horse example of Ontario education’s backwards approach to technology integration.

The second key piece in this is that we haven’t developed the digital transliteracy in our system to make remote digital learning a possibility. Complex tools like video chats require infrastructure and knowledge and familiarity to work. Our board doesn’t enable video chat in our Google apps for Education system for students, so expecting familiarity with it isn’t reasonable. It was difficult enough getting staff up and running on it. The teachers trying to meet that important psychological need Nam mentions are taking huge risks, possibly to their careers, by going cowboy with this.

For those of us comfortable in digital mediums video chat seems like a no brainer, but it depends on complex digital transliteracy and if you don’t have it, you can’t effectively make use of it. In that familiarity lies a hidden third layer that everyone is struggling with. Zoom bombing is another example of digital illiteracy at work and highlights the cybersecurity and privacy considerations that our system is truly oblivious to, even as we drive people into digital spaces. Zoom was a rushed, unencrypted communications tool that used toys to hook people into using it. A digitally transliterate user could set passwords and lock out Zoom bombing, but oblivious users didn’t and a company unfocused on cybersecurity exacerbated the situation.

For all its problems, Zoom does address one glaring issue that many other video chats don’t. The backgrounds you can put into Zoom would mitigate one of the major privacy concerns highlighted so well in this blog post by Alanna King. If a government run school system requires you to video in during remote learning, what are you expected to share? Video chats often show more detail than we’d like. We’ve all seen just how unprepared adults have been to use video sharing tools when working remotely (digital transliteracy is remarkably poor in the general population – which is probably why education is so slow to develop it), but when a government requires minors to show the insides of their homes and themselves remotely it should sound a lot of alarm bells.

A tech-fluent teacher was trying to set up video with his students in the opening weeks of remote learning and wanted to post the videos on YouTube. He was going to show student work on the video in a kind of lecture format. Using digital communications to replicate classroom experiences is one of the biggest failures in education. It shows just how stuck we are in our way of approaching learning, but that aside, are you, as a parent, comfortable with your child’s work being published on YouTube? Are you comfortable with Google making advertising revenue from it? In other cases I’ve seen teachers record video chats with students and publish them on YouTube. The same questions apply, but now they include, are you comfortable with your child and your home life being published on the internet without your say so or oversight? Are you comfortable with Google making advertising revenue from that?

We have the technology to close the gap Nam’s kids are feeling during this pandemic, but we haven’t developed the technical skills or clarified the social expectations needed to do this effectively with adults, let alone children. That all of this technology is trotted out by tax dodging multi-national technology corporations whose main intent is to monetize your attention is just another layer we haven’t bothered to wade through.

“While it’s the right thing to keep schools closed, learning from home is not working for all Ontario students, and that’s why the government needs to follow other jurisdictions, such as New Brunswick, and cancel the rest of the school year.”

I had mixed feelings about this. I’ve hurt myself trying to make this work. My digital expertise is abused and ignored variously and inconsistently because I suspect it has never been valued by the system. I’ve agitated for supports for students and staff based on this complex and evolving situation even as the system has stumbled from one inconsistency to another. My self-selected group of digitally transliterate students are the tiny minority who volunteer to take my optional courses (I teach less than 10% of the students in my school). I don’t have the digital transliteracy issues other teachers are battling with, but then the mental health and socio-economic problems became apparent. Students passing out at work and clocking 50+ hour work weeks while being expected to produce hours of school work seemed cruel and inhuman. Seeing my own family bending under the stress of this ongoing crisis means I can’t do my job as effectively as I usually do as well.

Nam mentions elsewhere the lack of report cards and missed days of school this year. I can’t help but feel that this remote learning caper is just the latest cat and mouse game being played by a government that is still very much intent on dismantling public education so it can sell it off to friends and family in the private sector. Whether it’s driving for elearning contracts with multi-nationals or just crippling our classrooms to the point where private schools seem like a viable option, I’m exhausted by this intentional mismanagement. Maybe pulling the plug on the whole thing is the right way out, but if it is you can bet that Lecce the cat isn’t done playing with us yet. And I hate the idea of giving up. Perhaps, as Nam said, this time could be better spent training and enabling our atrophied digital transliteracy instead of stressing families.

Nam mentions elsewhere the lack of report cards and missed days of school this year. I can’t help but feel that this remote learning caper is just the latest cat and mouse game being played by a government that is still very much intent on dismantling public education so it can sell it off to friends and family in the private sector. Whether it’s driving for elearning contracts with multi-nationals or just crippling our classrooms to the point where private schools seem like a viable option, I’m exhausted by this intentional mismanagement. Maybe pulling the plug on the whole thing is the right way out, but if it is you can bet that Lecce the cat isn’t done playing with us yet. And I hate the idea of giving up. Perhaps, as Nam said, this time could be better spent training and enabling our atrophied digital transliteracy instead of stressing families.

“When a board’s solution to a lack of Wi-Fi access to is to advise its students to access it via a school parking lot, maybe that should be reason enough to rethink our government’s e-learning approach.”

Even something as straightforward as this is a roll of the dice. Our board turned it off. Other boards have opened it up to the public. Even with something as clear as connectivity we have no central direction or organization. That sitting in a school parking lot is the best we can do says a great deal about how we approach the digital divide.

“We’ve also made assumptions about teachers. We assume that all teachers are tech literate and have set-ups at home to manage this work.”

Which isn’t remotely true. I stumbled across this OECD computer skills survey a few years ago and was flabbergasted at how poor digital transliteracy is in our population. Being at the top of that chart meant you could do simple things like take dates from an email and make an online calendar entry from them. It wasn’t even coding or IT know-how, just simple computer use, and most people are staggeringly ignorant of it. Teachers follow the rest of society in this regard.

Which isn’t remotely true. I stumbled across this OECD computer skills survey a few years ago and was flabbergasted at how poor digital transliteracy is in our population. Being at the top of that chart meant you could do simple things like take dates from an email and make an online calendar entry from them. It wasn’t even coding or IT know-how, just simple computer use, and most people are staggeringly ignorant of it. Teachers follow the rest of society in this regard.

I’m currently talking to other teachers in my school who are trying to navigate remote digital learning with 80+ students on a Chromebook with a 14″ screen. My digital fluency has led me to get the tools I need to interact in digital spaces effectively, but for many others it isn’t a priority and they don’t have the tools let alone the digital transliteracy to make this work. When the system was doing back-flips to get tech out to kids who don’t know how to use it, few efforts were being made to do the same for staff.

Of interest in that survey, it turns out that younger people do have marginally better computer skills, but only slightly. One of the reasons we’ve done next to nothing in developing digital transliteracy in our schools is the asinine myth of the digital native – the idea that if a child is born in a time when a technology is in use, they’ll magically know how to use it – you know, like we all knew how to drive because cars existed in our childhood. This kind of nonsense has been used as an excuse to do nothing for decades now. I teach computer technology and I can tell you that students are as habitual in their use of technology as anyone else. They might be cocky and comfortable with laying hands on tech, but move them out of their very narrow comfort zone of familiar hardware and software and they are as lost as any eighty year old.

This crisis has shown me things I never thought I’d see: proudly digitally illiterate teachers participating in video staff meetings and kids performing feats of endurance for atrophied student minimum wages while being called heroes by the guy who reduced their minimum wage.

This crisis has shown me things I never thought I’d see: proudly digitally illiterate teachers participating in video staff meetings and kids performing feats of endurance for atrophied student minimum wages while being called heroes by the guy who reduced their minimum wage.

After the year we’ve had (and I won’t even get into how our family has had to fight cancer and limp along on partial salaries for months on end waiting for anyone to help us), I think I’m ready to put it down, I only wish this government would too, but I know they won’t.

I said it in response to Alex Couros on Twitter and I’ll say it again. Maybe the best thing that will come of this is that we’ll start to recognize what literacy is in 2020 and begin to integrate technical and media digital transliteracy into our curriculum for all students and teachers. Given time, we could develop a system that is resilient and able to respond to a challenge like remote learning effectively and quickly – completely unlike how this has gone down.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/3bQiRHJ

via IFTTT