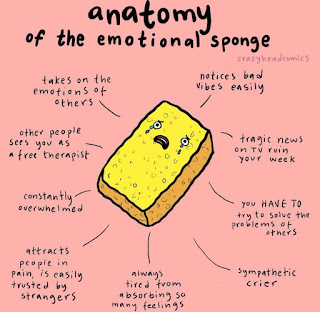

One of my strengths as a teacher is my overdeveloped sense of empathy. It’s also why I’m often exhausted at the end of a day. The recent state of affairs in Ontario education has gotten to the point where I have to time my exposure to this negativity as it infects my thinking elsewhere. I’m trying to balance the need to make political noise to stop the sociopaths in government with my own mental health.

The end of semester one happened and I came home one day hanging on by my fingernails. As is typical in most Ontario classrooms, I have a staggeringly wide range of students. My recent grade 9 class contained students who were functionally illiterate with others who are already operating two grades ahead of where they should be. I’m somehow supposed to deliver meaningful, differentiated instruction to all twenty five of them. This reaches peak pressure as the semester ends and these grade 9s, who have never learned in a semestered system before, struggled to understand that the course is ending and I won’t be their teacher any more. When my wife saw the state of me she said, “you’re a sponge” soaking up all of this stress and negativity.

The end of semester one happened and I came home one day hanging on by my fingernails. As is typical in most Ontario classrooms, I have a staggeringly wide range of students. My recent grade 9 class contained students who were functionally illiterate with others who are already operating two grades ahead of where they should be. I’m somehow supposed to deliver meaningful, differentiated instruction to all twenty five of them. This reaches peak pressure as the semester ends and these grade 9s, who have never learned in a semestered system before, struggled to understand that the course is ending and I won’t be their teacher any more. When my wife saw the state of me she said, “you’re a sponge” soaking up all of this stress and negativity.

Chasing the strays and getting marks in is exhausting, and often simply an exercise in damage control rather than a learning opportunity. Marking exams was also interesting. I share all the theory tests we did throughout the semester online and can see when students make use of them in studying. The vast majority of my grade 9s, 10s and 11s spent less than 20 minutes reviewing for exams. Our class averages typically landed at about 60% with 1/4 of each class failing. Even when you hand the actual exam questions over to students, a frustrating large number of them can’t be bothered to lift a finger to review it, though they all expect a good mark for it.

This is partly to do with the fact that we’re forced to do academic style exams to protect the academic style exam schedule, even though we’re an applied, skills driven course, but it also has to do with how modern students accept responsibility for their learning. They are repeatedly conditioned not to take on this responsibility. Attendance has become entirely optional – I have two students away on extended vacations at the beginning of semester two and I had many students with more than three weeks of absences in semester one. In addition to lax attendance expectations, students know that wherever possible their learning is done for them, often in line with standardized testing. This learning is neither individualized nor differentiated and does little to foster the life long learning that would genuinely assist students in the world beyond our classrooms.

I don’t usually look at the grades students are getting in other classes and without knowing I’m usually grading them similarly to their other grades in the building, but this semester I did look. Grades are up across the board. You’d be hard pressed to find a teacher that fails a student because they tend to get passed anyway in promotions meetings or given absurdly reduced expectations in a credit recovery class, so why pick the fight? That sense of helplessness is becoming an epidemic in Ontario education as a remorseless political group with dwindling popularity continues to attack a system most of them never participated in. I’m still ruminating on the connection between teacher efficacy and student learning outcomes. I suspect countries like Finland (and Canada before this neo-conservative press) offer a high level of teacher efficacy which leads to higher standards and stronger students. When the system thumps efficacy out of teachers, as it is right now, standards drop. It’ll be interesting to see if the data supports this in the coming years.

The crushing weight of all of this squeezes the life out of me at semester’s end. When it’s happening between intermittent strike days and the guy in charge of education (who was never in public education himself) repeatedly saying that we’re greedy and selfish, it all knocks me down yet another peg.

When I’m pressed under this kind of emotional weight, it colours my ability to assess the world around me. Things that probably aren’t that bad appear to be, but it’s hard to see that.

Last month I wrote a piece trying to work out teacher pay. I’m usually happy if a Dusty World post hits a thousand page views. For a specialist blog on education, I think that’s a good result. Easy Money is currently at just over thirty thousand page views and speaks to the curiosity that people have around the misinformation being spread in this political climate. That our Ministry of Education produced these misleading numbers is yet another layer of frustration. Teachers are still teachers if they are part time, on short term contract or away on sick leave, but our Ministry ignored all that and gave their political masters what they asked for – a misleading statistic that promotes their politics. I wrote Easy Money to wrap my head around a more nuanced and detailed understanding of the subject. That moment of over-attention chased me off blogging, which I’ve never done for views. Some of the things people say to you if you dare to challenge their politics is truly nasty. Dusty World has always been a place I can come and work out my thinking. If others benefit from that then great, but its function is to help me reflect on my own practice, not generate page views. Maybe in taking that back Dusty World can keep the darkness at bay in an Ontario drowning in deep blue rhetoric.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2UyKKy9

via IFTTT