Last March Break I attended an industry focused future of the workplace conference in Toronto. That event aggressively underlined the importance of micro-credentials in the modern workplace. The idea of years long programs, especially in technology where changes are happening regularly, suddenly feels like a lumbering has-been rather than a vital foundation to your workplace success. The same conference caused me to examine the purpose of public education (there is much more to it than simply preparing students for work), but the gulf between school and the world beyond our classrooms continues to expand.

Since then I’ve worked with ICTC on a badging system for Focus on IT students that would allow them to micro-credential their progress through the program. Anyone involved with the scouting program will know all about analogue badges well before there were any digital ones; badging has a long history of marking progress and expertise. The military has always used badging to denote rank and expertise. More recently badging has become popular in gaming culture to show skills and achievements and this has crossed over into the real world in terms of gamification of learning in education. Badging as a form of micro-credentialing is a cultural phenomenon familiar to everyone, so micro-credentialing is nothing new.

We spent the afternoon yesterday attending the 4th annual CAN-CWiC Conference in Mississauga. For someone who has been struggling against genderized pathways in his rural high school, attending a conference with hundreds of women in digital technology was like stepping into a future we may never reach where I teach, and isn’t the case in the vast majority of Ontario digital technology classrooms.

A couple of conversations prompted by the indomitable Alanna about how some of the women at the conference got into tech were very telling. We’re both on the pathways committee at our school and the divide between high school career planning and what’s happening in the real world was shocking. While we’re busy running a system that divides students by some pretty arbitrary standards and then builds up a marks history that defines student pathways into traditional post secondary learning, the rest of the world is struggling to find life long learners, something we only pay lip service to in our schools (don’t believe me? Find out how much PD time was spent on EQAO and how much was spent on life long learning). What we view as a static, established learning schedules (one the vast majority of teachers work in very successfully), is pretty much meaningless in 2019 beyond the walls of our ivory towers.

We just did a staff survey on the last PD day and the data aligned with my anecdotal experience in secondary education. When you fill a school with university graduates, many of whom have never worked in anything other than than the academic education system as either a successful student or teacher, you end up with a very blinkered view of the where the majority of our graduates go. Academics tend to overly value their own experience and encourage students to do the same. Students are directed to follow that long academic trajectory over developing lifelong learning skills valued elsewhere. The students that do follow it are considered ‘the best’ ones.

What is happening in the workplace? Digital disruption is rippling across all industry and is doing what it does, upturning traditional standards of practice and demanding agility before allegiance to tradition. In everyone we talked to at CAN-CWiC, traditional credentials were nice to have, but by no means were they the standard requirement they used to be. Industry people said that, sure, they have some post-secondary graduates in specific fields, but even in their case there was something that trumped any other credential: the willingness to adapt and learn more, even if you have a Ph.D.

What is happening in the workplace? Digital disruption is rippling across all industry and is doing what it does, upturning traditional standards of practice and demanding agility before allegiance to tradition. In everyone we talked to at CAN-CWiC, traditional credentials were nice to have, but by no means were they the standard requirement they used to be. Industry people said that, sure, they have some post-secondary graduates in specific fields, but even in their case there was something that trumped any other credential: the willingness to adapt and learn more, even if you have a Ph.D.

Danielle at IBM had a background typical of what many of our strongest female students experience. She did well in high school, and especially English, but took no tech because she wasn’t encouraged to take it – it isn’t what academic girls do. She went to the University of Guelph, ran the student newspaper, got a degree in English and then worked in radio as a writer for a couple of years until this shrinking traditional medium laid her off. She then found a ten week full time boot camp training program on full stack developing and is now a web developer with IBM Canada. She said that she greatly values her degree and time spent at Guelph and wouldn’t change any of it, but she wishes she’d had access to technology training in high school and university so she wasn’t getting into it with no experience in her twenties. Our tradition education systems plays to traditional stereotypes.

I had what I consider a feminist/woke colleague tell me about how her daughter is now taking bio-technology. I never saw her once in my computer engineering classes, but if it’s an academic girl aiming for university you’d be hard pressed to find anyone in high school telling them to take any applied technology course, even when that’s what they’re aiming at in post secondary. It’s much more important that all your classes end in a U and are in an academic situation (rows of desks) that prepare you for university. She’s now coding and is glad I put her on to Codecademy. That’s like being handed water wings when there is an olympic swim team you could have trained with in the building.

Whether talking to post-secondary education, skills training organizations or companies, the idea that we need to be able to quickly adapt in a rapidly evolving workplace probably sounds like it’s from another planet to an Ontario educator inured in our factory shift driven system. We aren’t skills focused, we’re shift focused. You might be miles ahead of what’s happening in your 3U maths class, but that’s your shift and you’re going to sit through it, for months on end. You might be miles behind in your 4U English class, but you’ll get passed along with the rest of your cohort with a mark that is pretty much meaningless. What does a 60% in 4U English do for you? What does a 100% in 3U math mean? It keeps you with your cohort and does very little in terms actual learning. We’re all held prisoner by our 19th Century education production line schedule that churns out grades. Every time the bell goes off to signal a shift change I wonder what year I’m in. But considering how difficult it is to timetable a grossly simplistic, generalized curriculum, I shudder to think what would happen if the system actually did need to schedule itself around individual student need.

Does this mean the end of traditional, years long learning programs? No, specialists still need that depth of training, but for many these years long, financially crippling programs aren’t leading to a job, so we have to change that expectation. I had a student last year who struggled in traditional classrooms but had good hands. He went to college because that’s what everyone expected him to do but dropped out in the first semester due to a lack of maths fundamentals (he probably got passed through everything with a 60% – gotta keep ’em with their cohorts!). My suggestion before and after all that was to start knocking out industry ICT qualifications and gaining experience in the workplace. Demonstration of your willingness to learn and evidence showing that you have a good work ethic will take you where a college diploma won’t. ICT is still a pretty new industry, so it doesn’t have the embedded, historically recognized apprenticeship pathways that other technology pathways do, but it should. Apprenticeship training with its mentored, skills focused, individualized learning is what the majority of applied training should be modelled around, but that system is foreign to all the Bachelor carrying people doing the teaching.

|

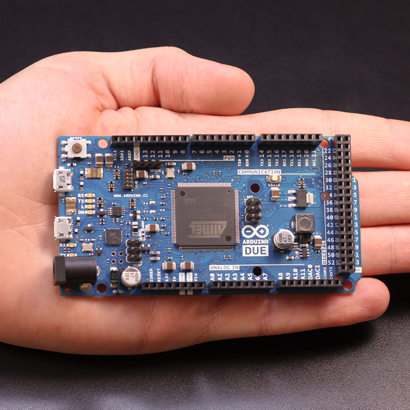

Nice eh? One of only a handful of people in Canada with

this qualification, but it doesn’t count in our

academics-only education system. |

After my degree I went to work in ICT and ended up getting my qualifications as a technician. Those were micro-credential bootcamp style courses I was taking way back in 2000. I AQ’d (AQs are micro-credentials) frequently when I started teaching and recently did two more ICT qualifications just to stay current and give my students access to material. OCT is very stingy around what it shows in teachers qualifications – mine shows only academic qualifications, but none of the technical qualifications including my apprenticeship because they are “less than” in our academically focused education system. Teacher training only matters if a university had a hand in it. Ironically, my board paid me nothing for my technical upgrading, even though it directly serves my students (thankfully my union did help me cover it).

Micro-credentialing is the new normal in the world beyond our school walls. A big degree or diploma also shows your willingness to learn, but if it’s all you’ve got in 15 years on the job, then most companies will ignore you. If you think it’s your passport to a good paying job, you’ll find yourself stuck in customs. Micro-credentialing shows an employer that you’re always willing to upgrade your learning and stay relevant in a changeable workplace. What they’re looking for is life long learners, not a one trick pony with a single degree or diploma from years ago, no matter what your grades. Aiming for an outcome like that (earn my degree and I’m set) is aiming for failure in 2019, no matter what grades you’re getting and how excited guidance counsellors are about your opportunities. If we were focusing our students on developing the confidence needed to always be open to learning something new, and the hunger and resiliency needed to leap into learning opportunities, they’d be in the right mindset to survive in the 21st Century workplace. Dragging unwilling kids through months of instruction isn’t doing that.

What this has done for me is underline all the extracurricular training and competition work we do in our program. All of those awards and the effort that goes into them highlights that go-the-extra-mile lifelong-learning skills that are so in demand in the world. That these efforts aren’t integrated into our curriculum is yet another failure of our marks based, traditional model.

What this has done for me is underline all the extracurricular training and competition work we do in our program. All of those awards and the effort that goes into them highlights that go-the-extra-mile lifelong-learning skills that are so in demand in the world. That these efforts aren’t integrated into our curriculum is yet another failure of our marks based, traditional model.

Maybe in the future Ontario classrooms we’ll begin to break down our schedules into micro-credentials. Students aiming at current and emerging technologies could take quickly updated, personalized, micro-credentials that focus them on the specific skills they need without months long classes. Traditional subjects like English could be broken down into their fundamental components. While everyone would need to take the literacy strand, not everyone needs to take the historical literature piece. What would our maths and sciences classes look like if students were working on particular, skills based micro credentials rather than grinding through months long, generalized curriculum aimed at a mythical average student? Digital disruption has produced differentiated production lines focused on more high value, bespoke products. Education could follow the same evolution and begin using ICT to differentiate student scheduling and specify learning so that it wasn’t locked into a pedantic and ineffective 19th Century model.

In 2011 I imagined a fictional account of what a system designed around student differentiation rather than enabling our traditional model would look like. The divide between what’s happening in our classrooms and the digitally disrupted workplace our students are graduating into has never been wider. If the various stakeholders in the education system can rejig the system while maintaining the highest standards (this isn’t about cheaper, it’s about greater flexibility in service of our students), then it needs to happen yesterday – we’re falling further and further out of relevance for too many of our students.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2X5iUsn

via IFTTT

As one of those vocational teacher types the ‘august disciplines” have yoked themselves to, I’m once again thumped in the head with just how classist the education system is, but it was a bit of a shock to see WIRED advocating it. I wrote about how there really is no such thing as STEM, at least in Ontario classrooms, in September. Nice to see WIRED weighing in on the pedagogical smokescreen that is STEM, though I don’t think they disentangled it very effectively.