1) Setup Anxiety

We just finished the final round of this year’s Cyberpatriot / CyberTitan Canadian Student Cybersecurity Competition. To say this year has been a challenge would be a gross understatement. We lost half our teams immediately thanks to COVID restrictions. The cancelled teams were both the junior teams who have missed a vital year of apprenticing with the seniors as we prepare for competition. Thanks to this break in our process we’ll be seeing a reduction in the skills we’ve systemically developed over the past three years.

With our two senior teams we limped through two rounds of the competition mask socially distanced to mask (because no one is face to face anymore) in our nerd lab at school.

The first round was shaky, especially on our senior co-ed team where our most experienced, senior students didn’t show up mentally on competition day. Some careful coaching and focusing got them on track for round two where both teams scored more like they’re able.

We just completed the final round of competition last Friday, and (because things weren’t already hard enough) this time it was fully remote thanks to Ontario’s systemic mishandling of COVID19. This had me up nights worrying about connectivity and tech at home for eleven competitors on two teams in eleven different home locations. Our student built DIY lab means I can take care of the complex setup needed to do Cyberpatriot and let the students focus on the material itself, but not this time.

The competition uses virtual images (computers simulated inside a window) that give students hands on experience with infected and compromised computers. When you open a virtual image and start working on it a timer starts and you’ve got six straight hours to maximize points by fixing the image. If one of your images doesn’t open or a student is having technical issues, you’re still on the clock and losing time. Doing IT support in a live environment with harsh consequences like that is very stressful, which is why I’d been anxious.

I delivered technology to students at home and did everything I could to ensure that they had what they needed. I said repeatedly, “don’t talk about what you’re going to do, rehearse it!” This was finally heard (after repeating it several times – teens don’t like to practice things) and students didn’t just think they were ready for Friday, they knew.

They sent me photos of their home setups, most of which were home made/DIY computers that we either made in our lab at school or they built at home using the skills they learned at school. That produced a level of satisfaction I hadn’t considered; this final round students were competing on technology they built themselves that they’d also done all the software setup on so they could then demonstrate advanced digital skills well beyond what Ontario’s atrophied digital skills curriculum asks.

Put another way, I’ve been presenting on Cyberpatriot/CyberTitan for several years and a number of teachers have told me they’d do it but the technical setup is too complicated. It wasn’t for the grade 10s, 11s and 12s at home last week. Maybe it’s time to integrate digital fluency into Ontario’s Teacher’s Colleges if we’re expecting every teacher in the province to be proficient in the medium.

2. Swimming with the Digital Fishes

I’ve talked about the power of authorship in understanding and developing a meaningful pedagogy around technology use many times, but this time we took things to a place where few dare to tread. As we prepared for this seemingly insurmountable challenge I didn’t tighten things into rote demands for compliance, I gave these students agency, and doing so gave me a peak into a world few teachers ever get to see.

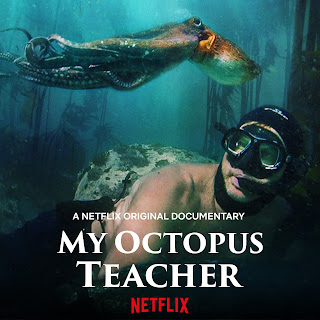

Thanks to Heidi Siwak’s suggestion, I watched My Octopus Teacher last week. What I saw on Friday in competition is much like what Craig Foster saw when getting to know his octopus: a wild animal being brilliant in its native habitat.

When you see students operating in the restrictive, overly prescribed walled garden of your corporately provided educational technology you’re seeing (in the ones that are actually digitally fluent because most aren’t) a wild animal in a restrictive, unfamiliar and domesticated environment. This produces a kind of reticence in the digitally fluent student that means you’re not seeing them as they really are when they operate in digital spaces. Even teachers with digitally literate students don’t often get to see this natural behaviour, which is expressive, efficient and astonishingly rich.

One of the ways we came to terms with managing the many challenges of trying to compete in a technically challenging international cybersecurity competition while stuck at home in a lockdown was by letting the students self-select the tools they would need to do the job. This started with making sure they were on technology that gave them the administrative privileges they needed to move freely. Nothing we’ve ever been handed at school was that. The other side of the equation is selecting the software we needed to be able to communicate quickly, privately and efficiently.

The students selected Discord as their communications medium of choice. I’ve had a passing acquaintance with this software but hadn’t been on it recently. One of my jobs as Cyberpatriot Coach is to proctor the teams and ensure compliance with the rules; I’m judge as well as coach. Cyberpatriot’s minimum requirements for fully remote competition only asked for a single check in with competitors but considering the circumstances (worldwide health emergency, remember?) I thought a bit more contact was in order.

The teams each set up private Discord chats focused on various areas of the competition. They couldn’t see each other, but I could quickly move between both groups and connect to live voice and video chats as well as screen sharing. This was vital in our approach to the competition as we encourage and depend on collaborative team interaction when problem solving. Other teams may like to do the loner hacker in a room by themselves, but we’ve never approached it that way.

One of the reasons for this is that I’m trying to raise digital skills in cybersecurity in a place where we started with nothing. To do that senior students work with the juniors when we’re practicing for competition (teams are physically and virtually contained during competition rounds). Collaboration isn’t just how we compete, it’s also how we learn the material.

Discord’s fluid and efficient communications environment not only allowed me to proctor the competition by easily moving between teams, it also let the teams design their own internal communications structures and then leverage them with astonishing effectiveness. Because they are all fluent in the medium their use of it is emotive and staggeringly fast.

While we were waiting for the email from CPOC to start round three (it never arrived, I had to contact Maryland directly to get access – my best guess is it got blocked by my work email – sigh), I watched memes appear and morph in the group chat. This was happening beneath continuous voice chats and screen shares.

Once competition began I was moving between the specialists on each team and then between the teams. I would drop into an ongoing discussion about how to solve a problem and immediately get a, ‘hey, King’ from the people in the chat. Discord has a little chime that goes off when you join a chat and the students are keyed to it. There is a misconception that teens aren’t engaged online but it’s because of how we situate them in educational technology, not because they are incapable of rich, interactive online engagement.

Over the course of the six hour competition I was flitting between discussions, but Discord doesn’t just make those discussions fluid and natural, it also lets you know what’s going on in them. At one point three students were in the senior team’s Linux chat and our two operators were both sharing their screens so that all three people could see them. This is precisely the kind of collaboration I feared we’d lose in a fully remote environment, but Discord made it possible for us to do what we normally do in a very difficult situation.

What made this potential disaster a success was DIY technology at home on self-selected communications platforms. We started and ended the day in a Google Meet on our board system and it managed to be both laggy and disengaging after Discord. Students never turned on webcams in Discord but because they could quickly and easily screenshare and emote in written chat while verbally communicating, they created an immersive and powerful online communications experience. On our stilted video chat at the end of the day I was left wondering why video chats are seen as the future. Like telephone calls, they’re the fixation of a generation, but not the future. If we weren’t spending all our time pressing students faces into their webcams on that limited video platform we’d be able to see how they actually swim in their digital sea and meet them there instead.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/39jQuTn

via IFTTT