I’ve been battling against digital illiteracy in Ontario’s public education system for going on a decade now and I’m frustrated at the slow rate of change. I’ve applied for multiple positions at the board and ministry levels and watched as future administrators get moved into these positions and fail to move the needle before they evaporate off into management. Perhaps my mistake is that I want to take on a curriculum enhancement role not to escape the classroom or to get myself into an office but to actually improve system response to an ongoing crisis that everyone else seems to want to sweep under the rug.

Considering Ontario’s current state of affairs, I’ll probably have to wait until after June 2nd for us to get a government interested in doing anything other than torturing our exceptional public education system into submission in order to hand a charter system for their donors. When Ontario comes to its senses (if it doesn’t, I think we’re moving), I’d really like to see us address digital illiteracy, but not just for the societal benefits it would provide – my actual interest is in developing a cyber-awareness curriculum that improves Canada’s ability to survive in a networked world while also clarifying this hidden pathway for students capable and interested in pursuing it.

Unfortunately, cyber and information security aren’t foundational digital abilities, they are advanced, complex skillsets that are developed on top of more simple fluencies. An academic comparison would be writing a complex essay of a challenging piece of writing in English class. In order to tackle the dreaded Hamlet essay, a student would need advanced reading skills with the ability to tackle complex vocabulary and grammar that includes an understanding of both poetic syntax and the chronological difficulties inherent in reading something over four hundred years old. This contextual challenge alone would stress most people’s language skills. On top of all that, the writing itself is a complex set of skills developed on top of simpler abilities. Students would need to understand spelling and grammar, and sentence construction and paragraph construction and argumentative theme development across the entire paper – it’s a staggeringly complex ask that we can only attempt in high school because we’ve placed literacy as a foundational skillset in our education system.

| That was in 2010 – over a decade later Schmidt is still trying to get people to understand the digital revolution that is happening around them. |

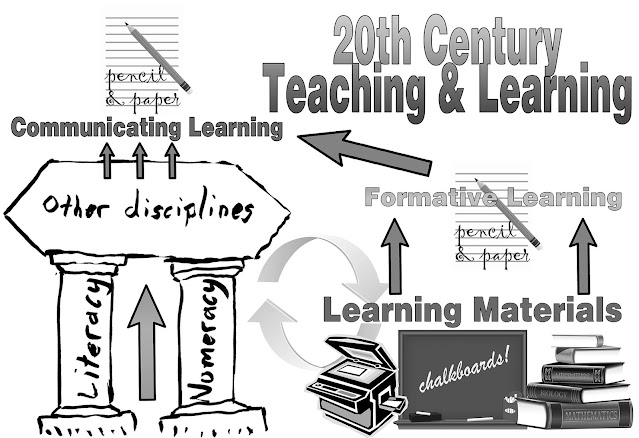

With that perspective in mind, I thought I’d try and take a run at infographicking how our

analogue education system has digitized over the past twenty years. This digitization of education has ramped up dramatically in the past decade – much of what I’ve written in Dusty World has orbited around this sea-change in digital teaching and learning.

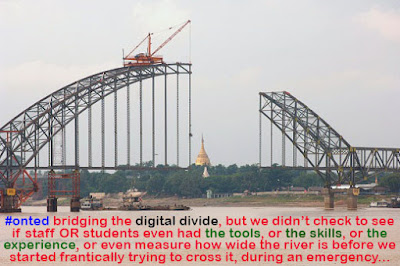

The suddenness of this change has left many people behind. There are administrators and ‘curriculum experts’ in our system who have never used the cloud-based learning systems we’re now required to use in every lesson. I’m up the pointy end of digitally fluent educators in the province. I applied for a system IT support role last year and didn’t get it – I suspect mainly because the system is incapable of understanding and appreciating digital fluency on anything but a puerile level; it’s a case of illiterate people failing to value and understand what literacy looks like; I’d really like to change that.

If we consider the education system I grew up in 1980s in Ontario, it was a very analogue place. Teachers hand wrote notes on the board, which we copied by hand onto paper (which many students promptly lost, assuming they made the notes in the first place). I can remember vindictive teachers doing a whole 76 minute period of note taking to ‘ready us for university’. Nothing prepares you for university like claw hand! These ‘lessons’ weren’t about how to take quality notes, they were about how to copy everything that was on the board as exactly and quickly as possible. In retrospect they did nothing to prepare me for university, but they were and example of the entrenched lessons we all experienced about creating analogue content; we never had a problem with teaching analogue skills because they hadn’t changed for generations. In the past two decades we’ve revolutionized information recording and access but we’ve also all but ignored learning best practices in these new mediums for teachers and students.

My generation has been described as ‘digital immigrants’ as we arrived at the current state of affairs from a time that would seem completely alien to anyone currently under forty years old. Along with the framing of us as digital immigrants comes the absurd framing of kids who have grown up in digital abundance as ‘digital natives‘. If you’re read Dusty World before you know what I think of this concept (it’s absurd – just because I grew up in a time with cars didn’t mean I magically knew how to drive!). What this lazy observation did was absolve education of the responsibility for teaching digital communications as a foundational skill, even as it became the basis for how we teach and learn. When I tried to replicate the 20th Century Teaching & Learning above with how 21st Century Teaching & Learning has become digitized, it quickly becomes apparent that digital skills aren’t just needed to communicate your learning (it’s even how we run the literacy test now!), they are also inherent in the learning materials you receive and the formative learning you are documenting. Many parents struggle with the new digital means of communications from their schools (online reporting and such) because of their own digital illiteracy. If you aren’t digitally fluent, you aren’t capable of learning in an Ontario classroom in 2022. You aren’t capable of teaching in one either, though that’s the new expectation in our on again off again emergency remote classrooms.

HOW TO ENGAGE EDUCATION WITH CYBERSECURITY

|

| https://prezi.com/view/7pqMzlLdfOFltD78ILP6/ |

Having worked with CyberTitan and Field Effect (an Ottawa based cybersecurity provider) on a joint federal government/private enterprise/public education presentation at the NICE K-12 Cybersecurity Education Conference this past December, we presented on how with industry expertise, federal vision and provincial public education community outreach we could make cyber-pathways available to all pathways interested students while also offering immersive and meaningful cloud-based simulations that are equitably available to all.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/32s5Qol

via IFTTT