I’m a teacher with a lot of technical expertise. I don’t just teach effectively with digital technology, I teach the subject itself. Fifteen years working in information technology in roles ranging from systems implementation to technical support and training are what led me into teaching the subject. When I began teaching in 2004 elearning was beginning to evolve out of distance (ie: mail order paper based) material. I jumped on it the summer after I started teaching at Peel DSB. At that point elearning was a very loose HTML webpage where you had to write code to display the content properly. I had some very interesting experiences teaching senior, university bound English on that system. When I moved to my current board I volunteered for their pilot elearning program and taught a variety of elearning courses purely online, and then did a blended face to face introduction to elearning while teaching the mandatory career studies course. One of the best things to come out of that project was that all of those students had a very clear idea of whether or not elearning would work for them. A third of the class never wanted to see it again, and the correlation between students with IEPs and students who had trouble with elearning was nearly 100%.

All that to say, I’ve spent a great deal of my career exploring how digital technologies might augment our teaching, but I’m also well aware of the shortfalls.

The recent pandemic shutdown has driven a lot of teachers and students online, and the framing by our Ministry early on was very elearning focused, but a colleague in our first ever staff video conference said something that resonated for me: this isn’t elearning, it’s isn’t business as usual, this is emergency response remote learning – we’re not ‘going online’ we doing everything we can to keep education alive at a time when it’s too easily dismissed. This might sound like an arbitrary distinction, but it isn’t. Not everyone needs to go online, and in many cases (as in the 2011 career studies experiment above), we have a sizable portion of our student population who cannot learn effectively in that space. When you also toss in the inequity of online learning, it leaves option looking like a very poor go-to. As educators, whenever we see the system roll out an undifferentiated, blanket response to an issue (like EQAO), we should take a hard pedagogical look at it. Uniform responses that don’t honour our student (and teacher’s) individual approaches to learning and teaching are, by definition, unresponsive and ineffective.

Since the school closures happened, I’ve been very conscious of the economically disadvantaged students who have been cut off at home. This may very well be a home that isn’t safe, isn’t providing adequate care and isn’t where the student wants to spend their time. The “stay at home” message that started this off is couched in privilege. For many students home isn’t a nice word. I’ve been frustrated by the lack of initiative shown in this crisis, but the digital divide many of our students face was something we could have addressed before, but didn’t. Some leaders are now using that lack of equity as an excuse to do nothing, which strikes me as the worst kind of hypocrisy. If we messed it up before, we’re messing it up now for even more people because what we didn’t do before is an excuse to do nothing now? Wow.

Since the school closures happened, I’ve been very conscious of the economically disadvantaged students who have been cut off at home. This may very well be a home that isn’t safe, isn’t providing adequate care and isn’t where the student wants to spend their time. The “stay at home” message that started this off is couched in privilege. For many students home isn’t a nice word. I’ve been frustrated by the lack of initiative shown in this crisis, but the digital divide many of our students face was something we could have addressed before, but didn’t. Some leaders are now using that lack of equity as an excuse to do nothing, which strikes me as the worst kind of hypocrisy. If we messed it up before, we’re messing it up now for even more people because what we didn’t do before is an excuse to do nothing now? Wow.

I’m also staggered that there is evidently no one in the largest school system in the country who is responsible for emergency response planning. We seem to be making it up as we go and delivering planning by press conference, and we’ve already lost three weeks to plan something that should have been in place from the go. You know what’s harder than teaching remotely? Teaching remotely using constantly changing expectations.

So here we are, in a pandemic situation that people have been warning is coming for years. Our solution is to throw elearning at it, and (so far, 3 weeks in) do nothing to address the fact that thousands of Ontario students don’t have the devices at home and/or the internet connectivity to access it – and those are the students who most needed education to support them from the beginning.

There is a reason why we truck in students on diesel fume spewing school buses each day to a face to face learning environment; public education is the great equalizer. More than anything else it helps us find the best in our population and enable them to achieve beyond the socio-economic situation they find themselves in. For wealthy students school can feel like a step down from a life of choice and excess, but for others it is a bastion of reliability; the only time in their day when they’re talking to dependable, capable adults. For some it’s the only time when they aren’t hungry, and our solution in an emergency situation that demands isolation is to ignore them?

|

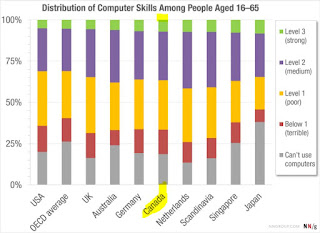

Level 3 means you can take a time and date out of an email

and put it in an online calendar, this isn’t rocket science,

and yet most people aren’t even there. |

Let’s say we get the digital divide under control and manage to get everyone connected (we haven’t and we wont’, but let’s imagine we did). Now that we have everyone online and using an appropriate device, we need the majority to leverage digital skills they haven’t developed and get them learning remotely. Ontario doesn’t have a digital skills continuum, other than some vague language dropped into other subjects here and there, yet we were increasingly expecting students and teachers to use digital tools in school and now they have suddenly become a necessity. I teach computer technology and have a well developed program, but I only reach about 100 students out of the 1300 in our school. If you count the business tech courses and media arts that also build digital fluency, all together we’d be lucky to reach a quarter of our student population, the rest have basic, habitual digital experience – like most of the population. What we’re doing with elearning is akin to handing out books to illiterate people so they can learn at home with them.

Could elearning work? It has in my experience, and I’m seeing some of my very digitally fluent seniors doing outstanding work online now. I’ve had some very positive elearning teaching experiences where we leveraged technology and created a remote learning environment that was rich and responsive. When it’s happened it was with a digitally focused and experienced teacher and voluntary students who also had the resilience and technical expertise to make it happen. When you teach online it feels like you’re looking at your students through a wrong-way-around telescope. I described this recently in terms of bandwidth. When you’re face to face with someone you’re able to read their body language in fine detail. The tone of their voice isn’t a dimensionless thing coming out of a tiny computer speaker, but it doesn’t end there. I’ve had students with obvious (when face to face) hygiene issues that I’m able to notice and subtly address by getting our councillors involved. I’m able to leverage the fantastic food school resources our school offers to get hungry students fed when we’re face to face. I’m able to overhear student conversation in class that gives me the context I need to connect with them more effectively. I’m able to present body language and nuance of voice that develops trust and a human relationship. I’m able to differentiate instruction with students quickly and effectively while face to face. I’m able to close the digital divide for all my students when they enter my lab. There is a reason we learn best face to face, it has way better bandwidth than any digital option. Even if you and your students are digital ninjas, remote/online learning is always going to be a lower bandwidth, less effective option that face to face learning.

In a perfect world we’d develop our staff and student’s digital fluency and engage in augmented 21st Century learning using digital tools and connectivity to enhance our ability to collaborate and communicate (and be ready for bizarre emergencies like this one), but it makes for a poor replacement; educational technology for augmentation is a worthy pedagogical goal. Educational digital technology replacing face to face learning isn’t pedagogically motivated, it’s usually tied to scalability and the resultant monetization of a platform, usually with an eye to reducing costs. The elearning push by Ontario’s current government was entirely focused on this without any thought given to the digital divide, dearth of digital skills and pedagogically reductive nature of remote elearning.

This pandemic has shone a harsh light on the inadequacies of our system in terms of emergency response and digital skills training, as well as highlighting the ongoing digital divide. A good that might come of it is that we begin to address all of these issues and build a more resilient and effective education system that is able to take initiative and respond to an emergency situation without taking a month to think about it.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/3aGcQwG

via IFTTT

Since the school closures happened, I’ve been very conscious of the economically disadvantaged students who have been cut off at home. This may very well be a home that isn’t safe, isn’t providing adequate care and isn’t where the student wants to spend their time. The “stay at home” message that started this off is couched in privilege. For many students home isn’t a nice word. I’ve been frustrated by the lack of initiative shown in this crisis, but the digital divide many of our students face was something we could have addressed before, but didn’t. Some leaders are now using that lack of equity as an excuse to do nothing, which strikes me as the worst kind of hypocrisy. If we messed it up before, we’re messing it up now for even more people because what we didn’t do before is an excuse to do nothing now? Wow.

Since the school closures happened, I’ve been very conscious of the economically disadvantaged students who have been cut off at home. This may very well be a home that isn’t safe, isn’t providing adequate care and isn’t where the student wants to spend their time. The “stay at home” message that started this off is couched in privilege. For many students home isn’t a nice word. I’ve been frustrated by the lack of initiative shown in this crisis, but the digital divide many of our students face was something we could have addressed before, but didn’t. Some leaders are now using that lack of equity as an excuse to do nothing, which strikes me as the worst kind of hypocrisy. If we messed it up before, we’re messing it up now for even more people because what we didn’t do before is an excuse to do nothing now? Wow.